Being blind

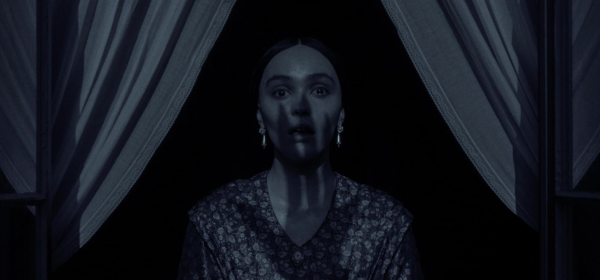

Laura White

English major Laura White sits on the couch at Oakland University’s Gender and Sexuality Center and looks happy. When students stop by at the little office in the basement of the Oakland Center and say hello, the 22-year-old senior who volunteers at the center and will graduate in May, recognizes them by their voices.

White has been blind since birth. Because she was born three-and-a-half monthes too early, her eyes never fully developed and the retina didn’t connect to her optic nerve.

“The doctors tried to fix it but it didn’t work. The visual signals go through, but the optic nerve doesn’t transmit them,” she said.

Even though she is blind, White can do most of the things other students do. “I don’t think I am so different,” she said. White goes to classes, writes papers on her computer, is involved in campus activities and surfs the Internet.

“I am a Facebook junkie,” White said laughing about her favorite website. To update her status, check e-mails or read other online pages, she uses JAWS, a screen reading software for blind or visually impaired people that also works for other computer programs.

Going to the movies or seeing one at home is as normal for the blind student as it is for others. She just watched the popular movie “Twilight.” “I saw the movie,” White said and explained that she doesn’t mind the expression. She listens to movies, pictures the plot inside her head and asks in case a scene confuses her.

Originally from Trenton, White lives in the student apartments on campus and travels with a cane to get around and to go to classes. “There is no way that you end up in the pond. The geese are a good sign teller,” she laughed.

Unlike Dave Barber, a blind OU student majoring in social work who has a leader dog, White decided to travel with a cane when she was younger. She didn’t want to be responsible for a dog while being at college. “My cane doesn’t have to go to the bathroom,” she joked.

Because White has always been blind, she never experienced how colors look. As a child, she was taught that “red is a like an apple, purple is like a grape, blue is like the sky.” “It’s hard to understand colors,” she said.

Still, not being able to see what colors look like doesn’t mean that she can’t be creative. White likes knitting and calls it her stress relief. “I kind of cheat,” she said because she uses yarn with different colors. “It’s a lot about feel – you don’t have to see your stitches to go into the next space.”

Angela Chezick, a 19-year-old freshman who is still undecided about a major, is friends with White and often meets her at the Gender and Sexuality Center during lunch break. “I admire her because she has changed the world around her to suit her needs,” Chezick said about her friend. “She cares about you as a person and not about what you wear or how you do your make-up. It’s kind of rare to find a truly good person like Laura.”

When people meet a blind person, they often don’t know how to behave. Once White went out with friends and the waitress asked “What does she want?” as if the blind woman couldn’t hear her. Other times, White can feel when people ignore or stare at her. “It’s not painful, it’s just upsetting,” she said. To promote understanding on campus, she and a friend founded the student organization STUD – Students Toward Understanding Disabilities – at OU last year.

“The worst thing you can assume is that blind people need help every time,” she said. “I am okay if people ask ‘Do you need help’, but don’t grab my arm and pull me in a direction.”

White has a map of campus in her mind. If she doesn’t travel by foot, she gets a ride from family or friends or takes the bus. “I wished I could fly,” she said. Sometimes she is jealous that she can’t drive by herself.

In her dreams, White can see. “I see pictures and people like everybody else. It’s my subconscious. It’s unique to blind people,” she said. Even though she can see in her dreams, there is something she is sad about. “When I’ll have children, I won’t be able to see them and won’t see how they change and get older.”

Asked what she would say if someone offered her the ability to see, White answered: “I probably won’t say no if someone offered me to see. I would have to learn everything from new and would freak out to see all these people.”

After graduating, White would like to work for two years for the Peace Corps overseas. Helping other people, developing sustainable programs and teaching English to children are important to her.

In her free time, she likes reading, singing and traveling. “I like to go to the West coast and see the ocean.” Even though she doesn’t really see it, she can smell the air, feel the wind and listen to the movement of the water.

Julie Edwards

Julie Edward’s story is different. The 24-year-old psychology senior lost her sight after a car accident three-and-a-half years ago. Edwards flew through the windshield because she wasn’t wearing a seat belt.

The impact injured her head and her brain started swelling. When she woke up in the hospital, she could still see. Then, one night, there was no nurse in the room and she got up to go to the bathroom. Edwards was weak and fell over, hit her head again and needed emergency surgery.

“They thought I was gonna die that night because my brain was swollen so much. After that, I couldn’t see,” she said.

Her optic nerve had been damaged . The first time she remembers being blind was at he Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan. “It was so weird, I didn’t think that I was blind. I swear, I thought I could see,” Edwards said. The doctors told her that people who become blind often have phantom sight.

“It was really hard for me to accept and everything. When I got out of the hospital, for a while I was really depressed,” she said. But then, Edwards decided that being depressed wouldn’t help her. “I thought I’ll have to figure out what I wanna be like being blind … so that I can move forward with my life.”

Before her accident, she wanted to become a nurse. She went to Michigan State for a year and then transferred to Madonna University to continue her studies. The consequences of the accident altered her plans. Without having sight, she couldn’t become a nurse..

Because the disability service at Madonna University wasn’t very helpful, Edwards started looking for a more supportive college, which was close to Dearborn and Dearborn Heights where her family and friends live. She decided to come to Oakland University and to major in psychology.

The accident changed the way Edwards sees life today. “I really did not care about a lot of things,” she said. “Now, I appreciate a lot more for what people do.” She explained that she took advantage of things and people before and that after losing her sight, her attitude changed.

“‘Amazing Grace,’ that’s my song,” Edwards said. Because of the way she lived her life before the accident, she especially likes the line “I was blind before, now I can see.”

When she moved back home into her mom’s house after leaving the Rehabilitation Institute, her family and friends supported her. Some of them needed a while to get used to the fact that Edwards is blind, but they didn’t turn away from her. She is still friends with all of them.

When she dreams, she is not blind and even drives in her car. “In my dreams, I am like I can see and my friends and family know it but nobody else is supposed to know that I can see. Everyone else thinks I am blind. I am not supposed to let people think that I am blind. It’s the weirdest thing,” Edwards said.

She tries to memorize how people looked when she had sight. Once in a while, she finds out that someone’s hair is much longer than before and then is surprised. “My worst fear is that I am gonna forget what things look like and that I will forget how letters and colors look like,” Edwards said. The only time she still handwrites is when signing her name and writing a birthday or Christmas card. For everything else, she uses her computer.

Two aids help her during the week with shopping and driving to places. In the meanwhile, she learned how to travel with a cane and moved into an apartment in Royal Oak because she doesn’t want to be any more dependent on other people than absolutely necessary.

Kristin Warner from Dearborn works for Caregivers at Home and has spent most of the weekdays with Edwards for the last two years. “I’d say, we developed a friendship over the two years because we are close in age,” said the 26-year-old. She appreciates that Edwards gives her a different perspective to look at life and how to solve problems. “I get frustrated with little things and Julie tells me that there are worse things that can happen.”

Even though Edwards has found a way to deal with her blindness, having her sight back is her biggest dream. Before the accident, she dreamed about being rich, but that dream changed. “I would be so exited. I wish I could see so bad.” She said she doesn’t think about it so often, but once in a while, someone asks her and then she does.

Photo by Brooke Hug/The Oakland Post

Shown: Laura White (left) and Julie Edwards