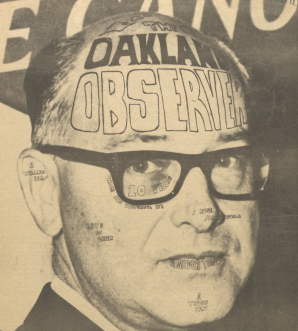

Professor receives high honor

At the front of the banquet room, a special bouquet sits on the center table where an honored guest, a small gray-haired woman is seated. She is the recipient of the 2009 Distinguished Professor Award at the Faculty Recognition Luncheon held last month. When she rises to accept the award, the audience rises to give her a standing ovation.

Approaching 80 years of age, Professor Judy Brown, the oldest faculty member at Oakland University, swims 1,000 yards a day, five days a week. She has also been swimming upstream most of her life against cultural norms, against unspoken rules about what a woman can or can’t do. For the most part, she has ignored those rules.

Brown, a professor in the department of sociology and anthropology at OU, has been teaching here for more than four decades and has co-edited and written numerous books and articles, mostly about women and their culturally-defined roles. At the faculty luncheon she was described as a trailblazer in the anthropological study of women’s lives in societies across the cultural spectrum.

Brown said that anthropology is the study “of all human beings wherever they have been.” Laughing, she said, “It’s a very modest agenda.” She said when you tell someone you’re an anthropologist, they always think that you’re Indiana Jones. (Archeology is a subdivision of anthropology, which might explain the confusion.) Brown says she is an archival anthropologist, which means she doesn’t work in the field. “I’m a disgrace to the profession, I don’t like to travel much,” she said. “I like just going to a library.”

Brown, who went to Harvard to get her Ph.D, said at Harvard she was fortunate to have access to the Peabody Museum Library, probably the world’s best library of anthropology.

Facing adversity

When she arrived at Harvard in 1950s, Brown said there were very few women. “I would walk into the graduate dining hall and there would be 200 people sitting there and I would be the only female,” she said. Brown said there was only one female professorship at Harvard at the time, which was endowed to be occupied by a woman.

“That’s the way it was back in the 50s,” she said. Brown said that female graduate students knew they probably wouldn’t be as well accepted professionally as the men were. She said she just knew the rules of the game for women at that time were that you had to go twice as far to get half as much.

Brown encountered a similar bias when she came to OU. Her friend and colleague in the anthropology department, Professor Richard Stamps, said that Brown was one of the first women in the department. He said that it was very difficult for them to accept a bright, intelligent, articulate woman. He also said that she was discriminated against, most notably, in pay. He said that it was one of those blatant examples of the way the world really used to be.

When she first arrived, Brown taught an extension class at Michigan State University Oakland one night a week. She said she was paid only “a handful of rice” but that it kept her going. At least, she said, she was doing something professional. Despite her education, OU didn’t hire her right away. She started working at OU part time in 1964, in the sociology and anthropology department. In 1969, she was hired full time, as an assistant professor. In 1983 she became a full professor.

Published work

While at Harvard, Brown met the eminent anthropologist John Wesley Mayhew Whiting, who became her mentor and her dissertation advisor. She went to Harvard to please her parents, but she had no idea what she wanted to do until she took Whiting’s course:

“I had this epiphany. Oh my God. This is fabulous. This is what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

Having published a paper on male initiation rites, Whiting suggested that Brown do her thesis on female initiation rites. Brown’s thesis dealt with initiation rituals for adolescent girls in various societies.

Later, Brown examined women’s roles in food gathering. Her paper, entitled “A note on the division of Labor by Sex,” was published in the American Anthropologist. It has been widely cited over the years, in fact, as recently, she said, as just a few weeks ago.

Brown said that at the time she did the study, there were beginning to be some rumblings of a feminist movement but that it was not exactly powerful and recognized. She said that her article had a big impact, but she was surprised when she found herself being described as a feminist. She said, “I never sort of identified myself as a rabble-rouser.”

Stamps said that Brown led by example, that she was not the kind of person to march on the picket lines. He said: “I don’t think she was a Gloria Steinem kind, out working the TV and radio stations. She was more the quiet scholar behind the scenes. I think she was the example of the good work people did and could do.”

When she was in her 40s, Brown was asked to write a review of cross-cultural research on women and women’s lives. She discovered that nobody had looked at middle-aged women. She found in her research that life actually got better for women as they aged in non-Western cultures, but that in Western cultures, people think that middle-aged women are, “sort of a disgrace to the race essentially, that when females get older, they should just disappear.”

Later in her career, a friend asked Brown to look into the literature on wife beating. They ended up doing a study together and were surprised by their findings. Brown said wife beating is a universal custom and is widespread in America across socio-economic classes.

Brown said there’s nothing surprising about being interested in women’s issues. “I did publish one thing that had nothing to do with women,” a paper about Levi-Strauss, “but generally speaking, I enjoyed looking at things that are essentially about what’s going on with women because I’m one myself and I don’t fully understand men at all.”

About the future Brown said she has some ideas but, “I don’t seem to get around to doing any of them.”

Professor Peter Bertocci, Brown’s colleague in the anthropology department who nominated her for the distinguished professor award, said that Brown got the standing ovation at the luncheon, not only because it is the most prestigious award, but also because she’s been around for a long time. “A lot of people know her, and she’s very well liked,” he said. “She was a path breaker in several different ways throughout her career.”