Dueling sides see

The problem with Michael Moore is that he’s become too famous. Not too famous for his career, of course. As the most successful documentarian in the history of movie making, Moore still receives more critical recognition and box office numbers than anyone else in the genre. But he has become too famous for his films to reach their intended audiences.

Like him or not, the fact is you already have an opinion of Michael Moore. And though he’s seen by many as a champion for the people, constantly defending the rights of the poor, the weak and the forgotten against the evils and everyday hypocrisies of capitalism, there’s just as many who view him as a snarky, self-important blowhard whose ideas are dangerous for the economy and the country as a whole.

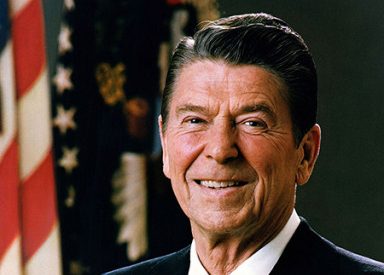

To be fair, Moore had a hand in making people hate him. One of his most famous films, “Farenheit 9/11,” has a premise that boils down to “Look how stupid the president of our country is.” And there’s a valid argument to be made there, because his stupidity led to disastrous wars in the Middle East and thousands of American lives lost. Still, it isn’t the best way to make friends on the right.

Of course, most of Moore’s films ignore politics altogether and discuss issues only as they affect the average citizen. Consider something like “Downsize This,” which points out the unfair way blue collar workers are allowed to be abandoned by companies they’ve been loyal to for years or even decades.

Or Moore’s last effort, “Sicko,” the premise of which is essentially “People should not be allowed to suffer and die from an inability to receive medical care, especially if those people are already covered by medical insurance.”

You would think such a unitarian and humanist viewpoint would be embraced by everyone, regardless of their political leanings. But look no further than the current health care debate — which, by the way, Moore himself had no small part in starting — to see that simply isn’t true. It seems anything Moore says will be met with both respect and rage, regardless of what he’s actually saying.

So, reasons Moore, why not go for broke and say precisely what’s wrong with this country and modern society as a whole? And thus, we have “Capitalism: A Love Story.”

The premise? Capitalism is an inherently evil, anachronistic and out-of-control system that is beyond repair and, therefore, must be destroyed. It’s essentially saying that everything the conservative right believes in is wrong, although that’s not to say it’s a Democractic film any more than it is a Republican one. In fact, Democrats receive some of the film’s harshest criticisms.

In “Capitalism,” Moore is offering a nonpartisan middle finger to the government, both left and right, who either argue for the ability of capitalism to bypass regulation publicly (Republicans) or who simply sign the checks in private (Democrats).

They’re both wrong, argues Moore, and it’s absurd to continue worshipping at the shrine of an economic system that can charitably be described as broken, and less charitably described as a sin — fundamentally opposed to the teachings of every major religion.

But he only hints at another option. He repeatedly calls for democracy, but what he’s really talking about is socialism — which is as democratic as any economic system could ever be — and if we can’t even socialize something as simple and essential as health care, how are we ever going to socialize the entire political and economic systems of America? It’s a problem Moore chooses not to address, probably because it’s such a losing battle there’s really no point in even fighting it.

As a film, “Capitalism” is decidely another Michael Moore movie, which is fine. He should do what he does best and, this late in the game, veering wildly off course would only seem like a cop-out. So expect lots of archived footage and personal stories told under Moore’s narration.

But there is an absence of the now infamous Michael Moore stunt, and the ones that made it in (like attempting to make a citizen arrest of the CEOs of the largest banking corporations) probably should have been left out. They don’t sell his point nearly as well as the true stories he tells.

And those stories do sell his point, incredibly well and in heartbreaking detail. But does “Capitalism” succeed as a rallying call? That still remains to be seen.

It’s an incredibly effective film: It explains and backs up its hypothesis well and it’s entertaining in the process. But the film ends in what seems to be a call to arms, directly addressing the viewer to take action in the citizen revolt Moore seems to think is soon coming.

And maybe he’s right. Perhaps “Capitalism” will pick up speed, people will see it and recommend it to their friends, families and co-workers and before too long a sizable portion of the population will be angry. Maybe all these angry people will quit their jobs and occupy their days instead by throwing trash cans through shop fronts and burning down chain coffee shops.

Maybe the capitalist system we’ve had since the founding of this country will be dismantled by the people, replaced instead with a socialist system so democratic and equal it resurrects Karl Marx from the dead like an even bushier-bearded Jesus.

Or maybe, the biggest reaction this film will see is a crowd of already like-minded moviegoers nodding their heads in agreement, and then going back to work at their minimum wage jobs, further inflating the stocks and salaries of multi-national corporate CEOs. Moore deserves credit for trying, but if this is the revolution, it’s just not going to cut it.