Veteran shares Iraqi stories

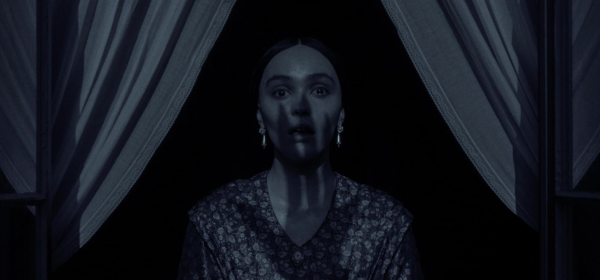

As Anysia Gray shares her computer photo album of her one-year tour of duty in Iraq, she remembers her feelings when she received the call telling her that she would be leaving for active duty on Dec. 26, 2004.

“We were supposed to fly out on Christmas Day so I wasn’t able to go home for the holidays,” she said.

A snowstorm delayed her departure to Iraq until the next day.

“It was very stressful, I didn’t even get to say goodbye,” Gray said. “I don’t know how to describe the stress you feel, and it was very somber.”

Gray, 27, who will graduate from Oakland University in May with a double major in sociology and women and gender studies, enlisted as an army reservist with the goal of earning money for her education.

She quickly moved through an experience that would change her life by exposing her to the stark realities of difference and loss.

Shipping out to Iraq

Her journey began when she signed up in February 2004 and attended fitness camp and basic training in March.

She then went on to Advanced Individual Training where she learned to operate dirt and earth moving equipment for the military.

There were 30 females and 120 males in her AIT. Gray was the only African American female.

It became apparent that some of the women in the barracks had never been exposed to women of other ethnicities.

“The girls in the barracks would ask really weird things, like, “‘Can I set your hair?'” Gray said. “I can’t say they were racists, they were just unaware and meant no harm. They knew I was from Detroit so they would ask me, ‘Have you ever seen anybody get killed?'”

After six weeks of AIT she graduated in August.

Her platoon called in September. She would be leaving for training to go to Iraq and had four weeks to get ready.

“I knew I could go to Iraq, but I didn’t think it would be so quick,” she said. “I had never been in for my weekend training — it was that quick. You don’t feel prepared.”

She completed her two weeks of weekend training and moved on to the Soldier Readiness Program in Minneapolis, Minn.

“That was when I knew it would be different,” said Gray. “I looked around and said, “Where are the people that look like me?'”

She spent October through December at Camp Atterbury in Indiana for more preparation and training.

Next, she was off to Iraq on the day after Christmas to join the 983rd Engineering Battalion in Operation Iraqi Freedom Three.

Gray’s first stop was Kuwait.

New experiences

After three weeks, her unit began a three-day convoy to Iraq.

“It was a horrible experience, and very dangerous,” Gray said.

Because of a lack of funds, only certain units received up-armored or fully-secured humvees. Others, like Gray’s, were left to make do with what they had. The humvee Gray traveled in had scrap metal welded onto it for protection. This was known as “hillbilly armor.” There was no bullet-proof glass on the vehicle.

Gray recalls sleeping on the hood of the humvee at night when it was cold.

When the sun went down, she said the temperature would sometimes drop 50 degrees. If it was 80 during the day, it was 30 at night.

The hottest day she experienced while in Iraq was 157°F.

“You would sweat, then dry up until your body got tired of it,” Gray said.

To stay hydrated she drank six liters of bottled water a day in addition to Gatorade and juice. There were no short uniforms. Gray spent her hottest days in full uniform with a 60-pound bullet proof vest.

As she continues through her photos, few women appear. In her engineering company of 137 soldiers, only 14 were women.

Gray felt women were treated differently — especially by the officers. Although her fellow soldiers treated her as an equal, she said the officers didn’t treat the women as part of the team.

Because of her race and gender, Gray sometimes felt singled out for small things. She received citations for infractions when others did not.

Living quarters were cramped. Six to eight women lived in the tiny barrack with what Gray describes as an “open floor plan.”

Arranged in rows, the little plywood houses had no interior walls. The women slept in bunks with three-inch thick mattresses.

The women hung sheets for privacy until they were told not to do so.

“It was worse for the men because there were more of them,” Gray said.

Life in Iraq

As a diversion, the soldiers were allowed to have fight nights and talent shows. The USO would provide occasional entertainment shows.

“You have to have fun,” Gray said. “You have to have something to keep you from going absolutely crazy.”

During downtime, Gray read books and played games like chess and checkers sent from home.

“I imagine this was what it was like before TVs existed,” said Gray.

They had TVs with DVD players, but no channels.

“I didn’t think about current events and I can’t say I missed any of that. What I missed was being able to get off work — you’re never off because you work where you live.”

Communication with family was restricted and kept in very general terms.

“You couldn’t let your family know where you were,” said Gray, “you would say, ‘Hi, I’m alive’ and talk about the weather or the movies. You get so detached, it’s weird.”

There were restrictions on social media sites and Army computers were only allowed to access secure websites.

Three members of Gray’s company were killed during their tour of duty.

One of her photos reminds her of a friend, Kendall Fredericks, 19, who was killed during a convoy to Baghdad. Gray remembers Fredericks made the trip to complete finger prints for his paperwork. His was crushed in the humvee when a roadside bomb exploded.

“He was a great guy,” Gray said. “I don’t know what else to say.”

“Most soldiers are killed in convoys … but you could die on the base. We got shot at every single night.”

She recalls two other incidents where soldiers were killed by incoming missiles.

One occurred while Gray was jogging. She heard the tell-tale “whistle” and knew a missile was on its way.

A marine, who was also jogging, was hit and his body blown to pieces.

“I kept puking, and running, and puking … and the worst thing is that nobody says anything about it.”

Gray later witnessed a bombing of a gym while she and her partner watered a cement helicopter pad (to keep the pad free of dust) one night. She described being frozen with fear as she heard the “whistle” and saw four people walking into the gym. There was no doubt in her mind the four were killed.

Gray served her one-year tour without a break.

“A lot of people went home for two weeks,” she said. “I didn’t.”

Gray said that if she left, it would have been too hard to come back.

And yet, Gray was able to find beauty in Iraq.

Looking at another photograph, she remembers the landscape, particularly “the most beautiful sunsets and sunrises. That was the only thing beautiful. It’s so clear when there’s nothing around.”

Returning home

As the end of her tour approached, Gray looked forward to returning home, but nothing is ever certain.

“They don’t give you a date,” she said. “You’re hoping that you’re out by a certain time. Rotation is one year. They don’t tell you anything, and you can’t tell your family.”

Right up until the time the soldiers board the plane home, tours can be extended.

Upon her return home, on Jan. 27, 2006, Gray said that she felt more “distant.”

“Nobody can really understand what you went through … they have to be there with you. Every tour sees something different.” She still talks by phone with her “battle buddy,” Jennifer, twice a week.

“You never fully reacclimate,” she said. “Your life changes … some nights, I can’t sleep at all.”

She has also experienced hearing loss caused by the noise and the vibrations of the heavy equipment she operated.

Although dreams of Iraq still haunt her, Gray looks forward to the future with the possibility of graduate or law school after she leaves OU.

She finds the best way to cope is to stay focused. In addition to her studies, she is involved in her church and finds joy in volunteering with Alternatives for Girls, where she has two mentees.

“I help myself through working with them,” Gray said. “It takes the focus off my own problems.”

Veteran community at OU

Anysia is not alone at OU. Veteran Liaison Michael Brennan said there is a large group of Iraq war veterans on campus — himself included.

Brennan served two tours in Iraq. He served as an aircraft mechanic in the army in 2003-04, then again in 2005-06.

He said the Student Veterans of OU hold weekly meetings every Tuesday and host monthly events — from basketball games to movie lunches.

An on-campus office veterans’ affairs office was established last fall. The Veterans Support Services office is located at 103A North Foundation Hall

Brennan says OU was recognized by GI Jobs magazine as being in the top 15 percent of veteran-friendly schools for 2010.

“OU charges in-state tuition rates for out-of-state veterans,” says Brennan. The university is also flexible if classes have to be put on hold because of service.

Brennan acknowledges that while women can find acceptance in the military, some still struggle to fit in.

As she looks back on her time spent at OU, Gray said her women and gender studies classes have validated her experience. She finds comfort knowing other female veterans are on campus.

“I’m not the only woman who went through this struggle,” she said.