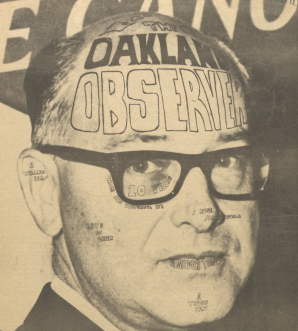

Looking back: February 1962 communism was OU’s hot-button issue

It is Feb. 3, 1962 in Rochester, Michigan. United States (U.S.) president John F. Kennedy has issued an executive order announcing a trade embargo on Cuba — a result of deteriorating relations stemming from the Cuban Revolution of 1953 to 1958 — driving Cuba ever closer to the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact.

A week prior, the Michigan State University Oakland’s (MSUO) — Oakland University’s name at the time — Young Republican State Charter organization passed a resolution condemning communism which read: “No Communist, foreign or domestic, nor any delegate or visitor from a Communist country be permitted to teach or speak on any tax supported campus in this state of Michigan.”

Earlier this week, Dr. James Haden — an associate professor of philosophy at MSUO — lectured on Marxism as a part of the university’s “World Report” series. In this lecture, Dr. Haden discussed why Marxism continues to be prevalent as a theory of governance, despite its failure in implementation within command economies. The facilitated pursuit of a sort of economic democracy and how that pursuit relates the individual’s role within the broader system of dialectical materialism were Dr. Haden’s main talking points.

In past years, U.S. relations with the Soviet Union have improved, at least in relation to U.S. relations with the world’s other Marxist-Leninist state, the People’s Republic of China. However, the U.S. and Soviet Union are still locked in a “Cold War.” Centered on state sponsored proxy wars, an international arms race and the stockpiling of nuclear weapons by both the U.S.-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Soviet Union-led Warsaw Pact, this simmering tension is based on ideological divides on the political distribution of resources.

However, within a month on MSUO’s campus, the Young Republicans called for a ban on speech for all communists, and subsequently were lectured by a university faculty member offering an interpretation on the very set of communist ideas that the Young Republicans moved to disavow.

In a time where the U.S.’ security dilemma is centered on the opposition of a set of ideas (collectively labeled as communism), a peculiar conflict arises. Which is deemed to be more important in a time of conflict: free speech or national security?

A rudimentary analysis of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution reveals that even if someone disagrees with an idea being propagated by an individual, the speech is likely protected as free speech. This also applies to discussion of ideas such as communism, and a ban permeating to even the most basic discussion of something such as communism would restrict the ability of an individual to exercise their right to free speech.

As an MSUO student in early 1962, one would have three choices to choose from in such an on-campus political situation. One may support the ban of people who believe in communism from teaching or speaking on the university campus. Conversely, one may support not banning people who believe in communism from being able to speak or teach at a college. Another form of participation in this civic process would be to do nothing.

Should the U.S. and its college campuses be a marketplace of ideas, adherent to the concept of free speech? Or should free speech be curtailed in order to protect against perceived anti-constitutional and thus undemocratic forces, similar to the German idea of “streitbare Demokratie?” Two questions students pondered then and still do now 59 years later.

This article was written using The Oakland Post’s archives. These archives are available to the campus community via the library in the front of The Oakland Post’s office.