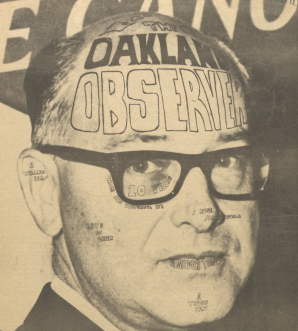

Professor abuzz with research

Just four hours after being born, were you able to recognize every single one of your family members?

Due to kin recognition, paper wasps, specifically the Polistes genus, are able to distinguish between family members and any intruders in their nests.

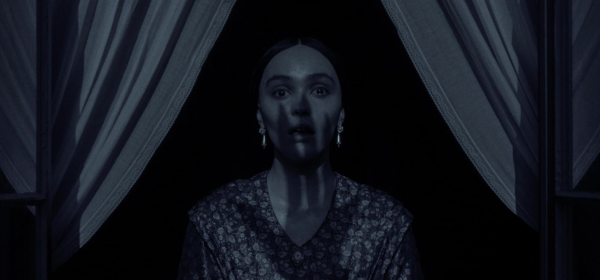

This is just one of the many facts that Dr. George Gamboa has discovered in his 30 years of teaching and research here at Oakland University.

Gamboa first attended graduate school at Oregon State University with an emphasis in marine biology. His education was postponed, however, when he was called upon to serve in the Air Force during the Vietnam War.

When his four years of service were over, he returned to America and his college education. He had lost interest in marine biology, but became more intrigued by behavioral biology.

His first animal behavior course, taught by famed insect behaviorist John Alcock, was the turning point of his career path. Given the option of taking a final exam or doing a class project involving research on leafcutter ants, Gamboa took the latter. After completing the project, he decided to do his master’s thesis on the subject.

Gamboa received his Ph.D. from the University of Kansas in 1979 and was hired by OU in 1980 as a biology professor.

He had always been interested in biology and the behavior of animals, but that fascination didn’t start out with wasps.

“I used to spend time at my uncle’s ranch and hunt some of the animals,” Gamboa said. “Eventually, I stopped hunting and took binoculars with me instead. I became interested in what they were doing and why they were doing it. That really piqued my interest.”

It was this early fascination with behavior in nature that has spurred a career spanning 30-plus years at Oakland University. In addition to his wasp research, Gamboa teaches biology labs, two different courses of Topics In Behavioral Biology, and Scientific Inquiry Communication.

With so much experience and knowledge in the behavior field, it’s not surprising that his students have found interest in his research projects and joined him.

“I needed a research project for my graduate work and I love insects, so it was a natural choice,” said Amanda Murray, one of Dr. Gamboa’s grad students. “I really like working with him because he is very knowledgeable about his work and has a passion for it. I have learned a great deal from him.”

About 10 years ago, that passion was put to the test. Gamboa began developing increasingly serious allergic reactions to the venom of the wasps when he got stung. Once these reactions became life-threatening, a drastic measure needed to be taken.

For five years, he had to receive anti-venom shots -— starting with mild doses and increasing to higher doses — and is now able to tolerate stings.

“I was at a point where I thought I would have to switch animals, because it became so dangerous,” Gamboa said. “When I was in the fields with the wasps, I was really getting paranoid because I knew I was going to have a serious reaction if I got stung. I never knew if I was going to make it.”

Some might consider a new profession after this problem. Gamboa, however, plans to continue with his research.

Gamboa and his graduate students are currently researching P. dominulus. This species has overtaken the native P. fuscatus as the most common species of paper wasp found in the United States.

P. dominulus had long been resistant to the various parasites that affected the native species, but recently has become more prone to infection by those parasites. Gamboa’s grad students will look into why this has begun to happen.

Gamboa and his students are also looking into aggression within hives and if that aggressive behavior is being passed on to future generations of wasps.

This extensive research is being done in the biological preserve, a 110-acre plot of land located on the southern part of Oakland’s campus. The entrance to the preserve is on a dirt road just off Pioneer Drive.

Walking around the preserve, one will find trees as old as 130 to 150 years, animals and insects of all different kinds, and 92 of Gamboa’s wasp nest boxes. These wooden boxes have a wire-mesh cover on them; this is done to keep out animals like raccoons, who would normally eat the larvae of the wasps.

Having been undisturbed for such a long period of time, the preserve has been able to keep its natural beauty.

“The preserve is truly an oasis in the middle of a highly developed area,” Gamboa said. “Sometimes you go back there and forget you’re in the middle of metro Detroit.”

After putting video cameras into the nestboxes, Gamboa and his students film the wasps for extensive periods of time, recording their behavior. Kin recognition, or the ability to recognize family members by odor cues, is one main focus of this video footage.

In addition to Gamboa and his Oakland students, the University of Michigan is also doing wasp research in the biological preserve.

Some might ponder the importance of Gamboa’s research. Other than describing it as “biologically interesting and significant,” he mentioned an economic aspect of the research.

“A lot of pest species, like yellow jackets and leafcutter ants, use kin recognition and odor cues,” explained Gamboa. “If you could somehow alter their kin recognition abilities so that they don’t recognize their own kin, you can cause them (the pest species) to self-destruct.