Ben and Baumbach, awkward and adult

Ben Stiller grew his hair out again, Chaz Tenenbaum-style, and that is something to be excited about. As the son of titular patriarch Royal Tenenbaum in Wes Anderson’s 2001 magnum opus, Stiller — for, perhaps, the first time — showed he was not only a funny character actor and competent director, he also had some serious acting chops.

Up until “The Royal Tenenbaums,” Stiller only came in two flavors: the down-on-his-luck everyman of comedies like “There’s Something About Mary” and the outsized caricatures of comedies like “Zoolander.” But in “Tenenbaums,” he was nuanced and guardedly vulnerable. Though the film was very much an ensemble piece, Stiller was arguably the heart.

Then, like other comedians who tried and succeeded in real acting (think Adam Sandler in “Punch Drunk Love” or Jim Carrey in “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind”), Stiller cut his hair and regressed back into his comfort-zone of constantly bemused straight men. His next starring roles, in fact, were in “Duplex” and “Along Came Polly” respectively.

Which is fine. A brother’s got to stay paid. But it’s a pleasant surprise to see him working with Anderson’s friend and frequent collaborator Noah Baumbach in his new film, “Greenberg.” And just as he fully transformed into an Anderson character before, Stiller truly seems like a Baumbach character here.

As Roger Greenberg, Stiller displays a lot of characteristics of the Baumbach model. His life isn’t going as he had planned, he’s afraid of the future and constantly groping for a past that may have never been. He’s also clinically depressed, obsessive compulsive and equal parts terrifyingly and comically short tempered.

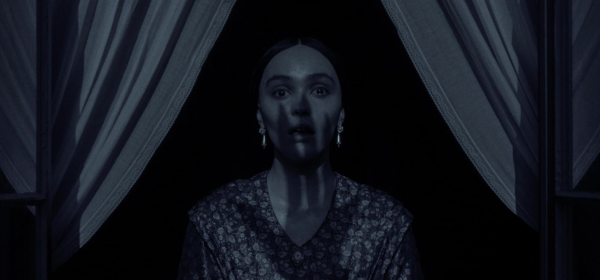

Yet he finds sympathy in his brother’s personal assistant, Florence, played with all the usual charm and casual grace of Greta Gerwig (“Hannah Takes the Stairs,” “Nights and Weekends”), with whom he shares a rocky and unlikely relationship. This personality clash to love connection may seem familiar, but Baumbach steers clear of traditional romantic-comedy territory. He never makes it easy for the characters to succeed, nor does he give much reason for the viewer to root for them.

Their meeting isn’t cute and silly; it’s awkward and vulgar. Their fights don’t lead to heartfelt apologies in the rain; they’re just left unresolved. And Stiller is never reformed; he remains just as difficult and unstable in the end of the film as in the beginning.

But there is a history established between Stiller and Gerwig, even if the future isn’t as certain. Like most of Baumbach’s films, “Greenberg” ends with a question mark rather than a period. “I don’t believe things happen for a reason,” Stiller says in one scene. “But what if this is happening for a reason?” Of all the themes Baumbach returns to, perhaps the most frequent is the concept that life never makes it obvious what’s supposed to come next.