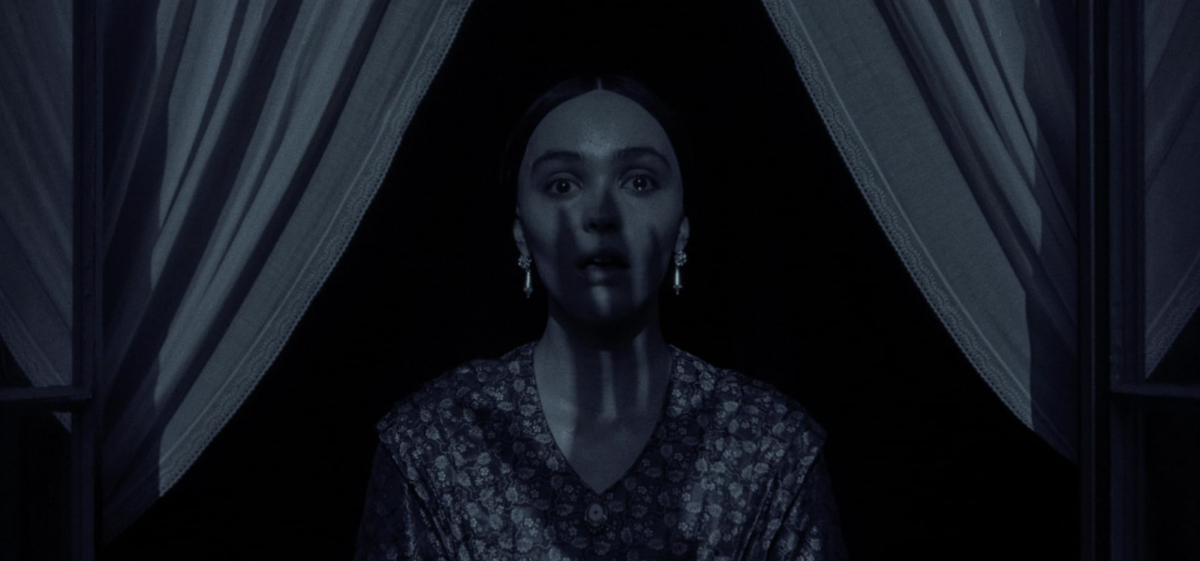

Beyond the memes mocking its overly sexual tone and the dozens of frames now adorning Pinterest’s goth vision boards, Robert Eggers’s reinterpretation of “Nosferatu” brings a deeply rooted analysis of gothic media.

More than a century after Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau created “Nosferatu” in 1922, Eggers crafts a film that explores and expands the vampire mythos — its eroticism, folklore and imagery.

The recounted story narrates Thomas and Ellen Hutter’s nightmarish love triangle with Count Orlok, a vampire who brings plagues and despair to 19th-century Germany.

Its horny horror combining monsters and eroticism doesn’t appear new, especially not with vampire stories. The original Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” and its eventual silver screen adaptation by Francis Ford Coppola were sexually charged with romantic triangles, lust-centered plots and the vampire’s inherent eroticism.

“A vampire penetrating your flesh with its fangs and exchanging fluids is a pretty obvious sexual metaphor,” Nyx Shadowhawk, a fiction writer, said to explain why vampires are sexy. “It represents a whole slew of different anxieties around sex, including but not limited to: loss of virginity or innocence, indulgence in taboo desires, and consent or lack thereof.”

Eggers breaks the glamorized “Interview with the Vampire” experience with a more historically accurate depiction of the living corpse introduced by Stoker. Of course, historical accuracy is no standard in a fantastical genre like gothic horror, but it does bring an interesting change to the eye-candy of neo-goth experiences.

By giving Orlok an awkward mustache, a not-so-sexy deep voice and a feral bloodsucking, all the erotic attributes of the vampire fall on his esoteric charm, giving the erotic-repulsion dynamic a more intense nuance.

This atmosphere is only achieved by the genuine exploration that Eggers conducted during pre-production.

“One of the tasks I had was synthesizing Grau’s 20th-century occultism with cult understandings of the 1830s and with the Transylvanian folklore that was my guiding principle for how Orlok was going to be,” Eggers said in an interview.

Integrating the Dacian language and deities on screen as part of Orlok’s character expands the cultural inspirations for an often Eurocentric gothic genre. Including Dacians, ancestors of ethnic Romanians, not only deepens the cultural exploration of Dracula/Orlok but also brings rich occult traditions omitted by prior storytellers.

With the detailed treatment of the characters and atmosphere, the raw portrait of Ellen and Orlok’s dynamic also reflects the expressionist nature of the story — extreme imagery and complex metaphors.

“In Bram Stoker’s original Dracula, the vampire represented the fear of sexual promiscuity in a time of increasing blood-borne STDs,” Ana Yudin, Dr. of Clinical Psychology and fiction author, said. “In Robert Eggers’s ‘Nosferatu’ the vampire represents death itself, Nosferatu’s pull-on Ellen reveals Ellen’s pull towards death as she becomes deeper and deeper entrenched in melancholia — depression.”

With a heavy emphasis on mystical imagery, Eggers’s prior works like “The Witch” and “The Lighthouse” expand genres like surrealism and folk horror with commentary encrypted in every frame — “Nosferatu” being no exception.

If the vampire figure represents the conflict between lust and consent, desire and love and the attraction-repulsion paradoxes in gothic romance, Eggers’s “Nosferatu” delves into the gothic horror of the science-occultism conflicts and the existential-moral interplay.

At its core, Eggers’s “Nosferatu” rummages about the dichotomies that flirt within the gothic genre — the grotesque and the glamorous, the enchanting and the shameful, the taboo and the desired.

Throwing a final rose to the expressionist tradition, the director leaves the resolution of this conflict up to the audience.

“Was it a sacrifice? You know, yes, but is there also some fulfillment there? As dark and twisted as it may be, yes. Is it also revenge? I think there’s intended to be a lot going on,” Eggers said.