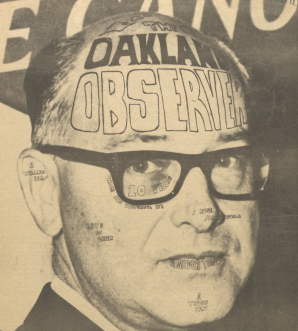

OBSERVER: You have been the Chancellor of Oakland for 10 years now; you have seen OU grow from a small college to a University; do you feel that the atmosphere for creative learning at Oakland has improved or deteriorated over these years?

VARNER: Actually, we are in our tenth year; it will be ten years next July 1. And, as the “younger generation” may not realize, Oakland’s first class of 570 freshmen had a sizeable proporation of “marginal students.” I would not want this to be a generalized statement, because we did have some very bright students. We had a strange mixture that year: we had bright students attracted here by the excitement of the curriculum; we had a larger block of students who were attracted here because it was convenient and inexpensive. These were students who were not quite sure they wanted to go to college, but had little to lose by coming here, since it was close-by, and they could live at home.

If you want to compare 1968 with 1959, there isn’t any question in my mind: The environment for learning and creative development is much better in 1968 than it was in 1959. We have a much more diverse faculty, we have a better library (although it isn’t good enough). We have a more diverse curriculum; we have a much wider range of student interest within the student body. I am personally convinced that Oakland, in 1968, is a much more productive learning center than it was when it first opened in 1959.

ORIGINAL PLANS ADHERED TO OBSERVER: Ten years ago, when the University was first conceived, some of the nation’s top educators met at the Meadow Brook Seminars on Higher Education to plan Oakland’s unique future. Some of thelr recommendations were to not compart-mentalize education by creating academic departments and to give a great deal of emphasis to Non-Western studies. How well has Oakland lived up to these and other recommended goals?

VARNER: In some cases we have lived up to the letter and to the spirit of the recommendations: In some cases we have lived up to the spirit, but not the letter of the recommendations: In some cases, I would say we have lived up neither to the letter, nor the spirit, of the recommendations. However, I was interested in something Professor Cherno had to say the other day. While looking at some of the early literature concerning Oakland University he had noticed how precisely Oakland University had developed according to those plans. There is a widespread attitude that Oakland has abandoned those early goals. He was surprised to find that we had adheared so closely to those early recommendations.

One area where we have departed from those early plans is the dormitories. When the plans were made, we were planning a small dormitory atmosphere here. Obviously, we have departed from this. I would say that in general we have followed closely the plans set up 10 years ago.

There have been some departures.

CHANGES IN LANGUAGE PROGRAM

The language field is an area of departure. I was, in the early days, one of the strong proponents of a program which makes it possible, perhaps even mandatory, that students who graduate from Oakland must be compitent in a field other than English. It seemed to me desireable in the world in which we now live. This is the goal we had when we first started Oakland. Students came to us not very well equipped to cope with this. Soon we found ourselves plunging very bright language professors into the business of teaching beginning languages. This was not particularly rewarding for them. It became apparent to us that students who came here with one year of language, or no previous language experience, were not very well equipped to move in a language program that would take them–by the time they were juniors to a level allowing them to study textbooks written in a foreign language. In the face of the evidence, which was so overpowering, we began to modify our standards somewhat. I think now we have substantial program, modified from the early goals.

CURRICULAR CHANGES

We’ve yielded in some other areas. The early curricular pattern was 3 courses-3 quarters. I felt then that 3 courses was a desirable course load. This was partly based on my own academic pattern and bias. At the University of Chicago, I found the three course pattern to be a much more rewarding learning situation. I’m not sure but what 2 or 3 courses, or even one, for a short period of time, is better than having 5 or 6. We started with a commitment to 3 courses, 5 credits each. When an experienced faculty arrived on the scene, they rather overwhelmingly voted this out.

I regretted seeing it go; although now I rather suspect that because of the growing complexities of the university, the 3 course, 3 quarter scheme would not have worked very well.

The Non-Western studies program is one that I felt a highly appropriate requirement. As you know, it has survived fairly well. I think it has been compromised bit. Not all students have to take the course. I suspect we still require more in this area than almost any school in the nation. I would still favor a year-long program in both Western and Non-Western studies. Our students should know our own heritage better as a basis for their own decisions and understanding in years to come.

THE IDEAL-SENIOR EXAM

I had favored, as written in the early curriculum, a required comprehensive examination for all seniors before they graduate. I still believe in this. This Is not an unreasonable expectation. Again, the faculty felt this would be a very difficult program to administer. Yet, I feel philosophically that there has to be some cohesion to the learning experience of students and that we don’t take prepackaged curriculum. There should be some unity to it. And if there is unity to it, then I don’t feel it is unreasonable to ask students to demonstrate their ability to attack a problem from a comprehensive viewpoint. I don’t envision an examination where you ask 77 questions and use a computer to rate answers. What I visualize is kind of ideal, and I suspect, Utopia. I visualize the assignment of a senior problem. The senior devotes a month, or perhaps two or three, to pulling together all the resources that he can muster. He’s had 7 semesters on campus. He has had several general education courses and courses in his own major. Now, he is about to gran duate with our stamp on him. I should think it would be quite an interesting program. He would demonstrate to us that he has learned something: he has learned to get at his sources. Hopefully, he will-rather than have his head crammed full of facts-have his head oriented to where facts are. He will be able to marshal facts and organize them. He can then bring them to bear on a problem.

I had hoped for this. I suspect we would have a chaotic situation with students who had gone through 7 semesters and came up to this comprehensive examination and we said, “Not good enough. We won’t graduate you.” The faculty pointed out the manpower requirements of counseling, guiding, and then examining the students. So that one was abandoned.

These are some of the changes that have occurred as we now look back on the last 10 years. While I may have some personal pangs of regret, I suspect wiser counsel has prevailed in these cases.

PROJECTED GROWTH

OBSERVER: Oakland began in 1959 with 570 students. Since then our enrollment has climbed to close to 5,000. A few years ago it was predicted that Oakland’s enrollment would reach

5,990 by 1969, 10,990 by 1974, and 20,090 by 1979. Given recent budgetary problems do you now expect that these projected enrollment figures will be realized?

VARNER: That is a difficult question to answer as there are many factors beyond our control in this picture. From my standpoint, and I think I speak for all the members of the staff and faculty, to be large has never been an objective of Oakland; to be good has. It seems to me inevitable that we will be large. This was an expectation in 1959. The early statements about Oakland University all indicated that we would undoubtedly grow to 20,000.

How fast we are going to grow is very difficult to forecast. So much of our growth pattern will depend on what happens in the legislature, the attitude of our board of trustees, the stance of the existing major universities: whether they curtail enrollment, whether they decide to grow rapidly. In some ways, I suspect our growth will hinge more on these factors, than any decision we may make. I am of the opinion that the legislature, and the board of trustees will expect Oakland to accommodate an increasingly larger number of the youngsters in Michigan who are getting ready to go to college. At Michigan State there are 40,000 students on campus, about 32,000 at Wayne and Ann Arbor, almost 20,000 at Western, 16,000 at Eastern, and we’re quite sure that within the next 10-12 years we will be asked to accommodate twice as many students as we do now. Oakland, with the land we have, and the location, will be large. We had projected the enrollment figures which you identified. I would guess we’re going to be pretty close to these.

“Liberal Arts College,” or “Professional Programs?”

OBSERVER: With the original emphasis on Oakland as a “small liberal-arts” college, why is It that the first doctoral program Oakland will probably provide will be in Engineering?

VARNER: That emphasis is the emphasis that was. It is one thing to talk about what Oakland will be, and another to talk now about what it was. Oakland was a small liberal-arts college the first few years. As things expanded, the professional programs emerged. Engineering has been a part of our commitment from the very beginning. As the years went by I learned that there are few, if any first class under-graduate programs in engineering where there is not a doctoral program. We found this out when we were looking for a Dean of the College of Engineering. The men we talked to made it abundantly clear that they have no intention of coming to a new institution, building a new program of engineering, if there was not a long-range commitment to building a doctoral program. This was simply because it was their notion that there could be no good under-graduate program if this were not carried to graduate level.

This statement is true in engineering more than any other department of our university. The evidence convinced me of this. In order to get our program to where it seemed to all of us that it had to go, it was necessary for us to make the tentative commitment that we will to doctorate programs. The timetable is uncertain, as you know. This must be discussed with a great number of people. But it is quite apparent to me that we must move to doctoral programs in engineering. I’m sure there will be other programs. Biology, the natural sciences, mathematics, are all I suspect, competent to deal with doctoral programs. There are some special areas in education that I feel may will have a good deal of Interest in moving to Ph.D. levels. We simply deal with these as they come along.