Campus workforce responds to AAUP allegations of university bad-faith bargaining

A view of OU AAUP supporters picketing during the job action that disrupted the start of the 2021 fall semester.

In January, Oakland University’s Chapter of the American Association of University Professors (OU AAUP) leadership released a letter they’d sent to President Ora Hirsch Pescovitz and the Board of Trustees (BOT) detailing revelations from a recent FOIA request that they say indicates the university bargained in bad faith during 2021’s faculty contract negotiations.

The university released a statement denying the allegations. Still the tone of the letter from OU AAUP President Karen Miller, in which OU AAUP alleges the university bargaining team, specifically interim Vice President for Finance and Administration James Hargett, withheld pertinent information about healthcare costs from OU AAUP during last year’s contract negotiations, raised eyebrows around campus.

In this article representatives from several on-campus labor groups discuss issues facing their respective groups and respond with their concerns about OU AAUP’s allegations that the university bargaining team bargained in bad faith.

Now the letter signed by Miller was virtually unprecedented in OU history and marked a new point of tension between faculty and the upper administration, as it featured a call for an investigation into the allegations and the employment status of specific administrators to be reevaluated.

“These actions constitute bad faith bargaining, violating the Faculty Agreement as well as both the National Labor Relations Act and the Michigan Public Employment Relations Act,” Miller said in the letter. “In an ethical and transparent organization, this type of behavior would result in employee termination. James Hargett, whose role in these actions has been clearly demonstrated, and any others found complicit, should not be allowed to continue in any capacity at Oakland University.”

The evidence OU AAUP provides that they say proves the university withheld information about healthcare costs consists of email correspondence between insurance providers and Hargett during bargaining.

Healthcare was a key issue during 2021’s contract negotiations. The idea that the university may have withheld information was alarming because fair negotiations rely on good faith exchanges of information.

“There are certain ground rules that are really fundamental,” Miller said. “You’ve got to be really naive to think that the stakeholders on either side of the table have exactly the same agenda. We can’t. Management and labor have different priorities … So we might get annoyed that they don’t appreciate our priorities, and I’m sure they feel annoyed that we don’t appreciate their priorities. But, it works. Bargaining works, because everybody’s operating with the same set of facts. Management has a dramatic advantage over access to information … this whole idea that [they] were going to keep information from [OU AAUP] … it’s just so 1930s, it’s so pre-Wagner Act.”

OU AAUP Executive Director Amy Pollard wrote and submitted the FOIA requests and co-wrote the OU AAUP’s letter that detailed how the evidence from the FOIA responses indicated the university bargaining team had withheld information on healthcare costs during 2021’s negotiations.

As a member of OU AAUP’s bargaining team, Pollard was fully aware of the significance of healthcare costs during negotiations, and says that discussions within the union about the new costs once an agreement was reached lead to her investigating the situation.

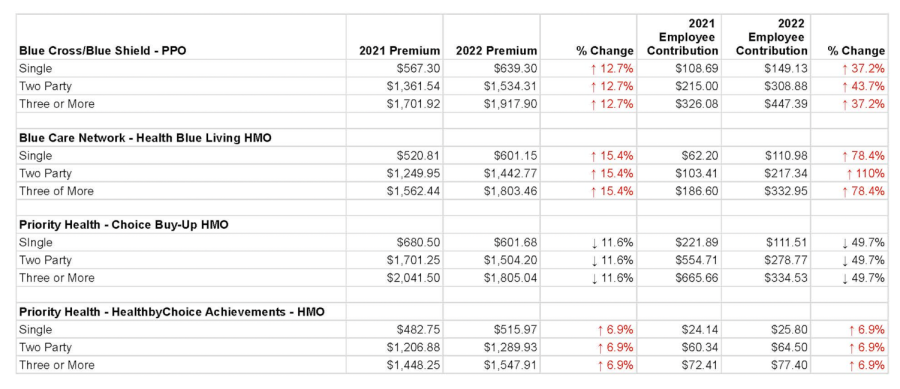

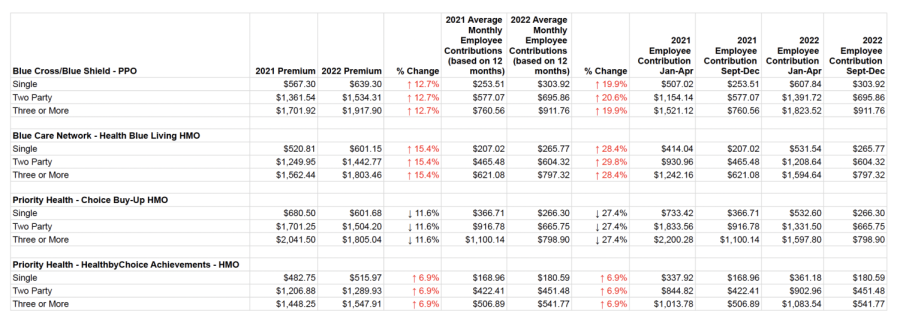

“For some faculty, their contributions went up 80% … So the employee contribution went up a huge amount,” Pollard said. “Once we got the final rates and we had to share them with everybody … it became clear that [the university bargaining team] must have had some information prior [to negotiations concluding].”

Sending the letter to Pescovitz and the BOT on Monday, Jan. 10, Pollard and Miller wanted some response from the university before notifying all OU AAUP faculty about what the FOIA requests had revealed. When after three days that response didn’t come, OU AAUP notified all their members of the letter on Friday morning. The response that did come from the university via The Post that following Tuesday, left a bad taste in Pollard’s mouth.

“I felt like we had presented pretty factual information and to be dismissed out of hand was disappointing,” Pollard said.

Pollard was not alone in being frustrated by the university’s response, with a feeling among faculty being that the bargaining team’s response was disingenuous and designed to avoid accountability from the administrators who were involved.

Given the negative feedback we were receiving concerning the university’s response to the allegations, The Post reached out to Pescovitz with a request to do an interview where she could address the situation.

That request was denied in an email saying, “This [The Post] is not the appropriate forum for discussing AAUP allegations regarding the collective bargaining process. That question was answered by the OU bargaining team statement provided to you.”

It is unclear at this time what the appropriate forum for Pescovitz, president of a public university and one of the highest paid public servants in the state of Michigan, to address allegations that her bargaining team cheated faculty during contract negotiations is.

It is worth noting that while the university bargaining team’s response did deny any bad-faith bargaining, it did not address the specifics of the allegations presented by OU AAUP. The response was also not signed individually by any members of the university’s bargaining team, which consisted of Vice President of Human Resources Joi Cunningham, Assistant Vice President Peggy Cooke, Interim Vice President for Finance and Administration James Hargett, Dean of the School of Nursing Judy Didion and outside legal counsel from law firm Dykema Robert Boonin.

While Pescovitz wouldn’t agree to an interview on the subject of OU AAUP’s allegations, an offer was made to do an interview with The Post later this month in which Pescovitz could “address the specific initiatives being planned that will foster increasingly stronger relationships between faculty and administration.” The Post is hopeful that that conversation will be substantive for the campus community.

So with these allegations, tension between OU AAUP and the university’s upper administration continues to be a story following last year’s contract negotiations, that much is clear. What was unclear was how other bargaining units on campus would respond to allegations that the university bargained in bad faith. It turns out that they are concerned.

In addition to OU AAUP, there are four other unions on campus that bargain with the university — Oakland University Professional Support Association (OUPSA), Oakland University Campus Maintenance and Trades (OUCMT), the Police Officers Association of Michigan and Command Officers Association of Michigan, and there are two substantial non-bargaining worker populations on campus — the Administrative Professionals and student workers.

OUPSA has about 250 members employed by the university. Their members perform a myriad of essential support roles in offices around campus. Their current contract is set to expire June 30, so they will begin bargaining with the university this spring.

OUPSA is currently on a one-year contract, meaning that like OU AAUP they also bargained with the university last year. OUPSA President Geoff Johnson says for them 2021’s negotiations weren’t what he expected.

“Last spring we were negotiating. [We were] looking at a standard multi-year contract,” Johnson said. “For us, a contract usually is either three or four years. We were getting told by the university ‘Yep, that’s what we’re looking at, a standard multi-year contract.’ But then right after Memorial Day, they came back with a ‘Well, you know, there’s been some change circumstances, things are tough. And all we can really do right now is a one year contract.’ So we ended up with a one year contract.”

In addition to the length of the contract, salary compensation was also a major issue for OUPSA during last year’s negotiations.

“All we got was a lump sum of $500,” Johnson said. “It’s certainly better than getting pay cuts. I’m not gonna make any claims that it’s nothing. But $500 doesn’t keep up with inflation.”

Johnson, who has now spent 23 years with OU, sees the university’s offers on compensation as an obstacle to OUPSA’s ability to hire and retain talented staff.

“None of us took a job thinking we’re going to get rich,” Johnson said. “But we thought it’s a good job [where] you get to help people out, and you’re helping students … and if you can have a good living, that’s great. But [our members are asking], ‘Am I actually better off than I was five, eight, 10 years ago?’ For many of my members, they look at it, and if they’re being honest, the answer is no. I think that’s a huge part of the reason that we’ve had a lot of job openings in the last year. Between the job market and everything else people are just going, ‘I’d like to stick around, but it just doesn’t make sense to.’ And we’ve had a lot of people leave.”

Regarding OU AAUP’s allegations that the university bargained in bad faith, Johnson had this to say.

“I fully believe what they’re saying,” Johnson said. “If they’re saying something’s [happened], it’s because something’s happened.”

He attributes this belief to his interactions with Miller and Pollard, as well as negative experiences he had as OUPSA president with the university at the bargaining table last year.

“I don’t like using this word, but it’s the word I used with them, they lied,” Johnson said. “… They told us all [raises would only come as] a lump sum. For all the groups other than faculty, that’s all that they were going to agree to … And then come October, they announced that the Administrative Professionals [were receiving a percent salary increase and a lump sum] … I’m not gonna make any claims [they] don’t deserve a raise, because frankly, I think they do …They’re working hard. It’s just the university told us that wasn’t going to happen.”

With a contract set to expire in November, OUCMT will also be bargaining with the university this year. OUCMT’s roughly 135 members take care of the manual labor on campus, and include essential roles like custodians, grounds crew and skilled trades.

OUCMT President Robert Vaughn points out how important their members were in keeping the university operational since the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our custodians play a big part in making sure that the buildings are clean and sanitized,” Vaughn said. “During this pandemic, they definitely have stepped up their game in making sure that our touch points are being sanitized and disinfected.”

For OUCMT, healthcare will be a major issue in their upcoming negotiations with the university. Considering OU AAUP’s allegations that the university bargaining team withheld information about healthcare costs, Vaughn had this to say.

“All the employees that help the university are concerned about these allegations,” Vaughn said. “If allegations are [proven] true, I’m confident that President [Pescovitz] will hold any persons involved accountable.”

Next to OU AAUP, Administrative Professionals (APs) are the second largest group of professional workers on campus with roughly 700 members to OU AAUP’s roughly 900. APs perform tasks all over campus at various levels within the administration.

“APs are really everywhere, and involved in everything from the academic side of the house, right to the Student Affairs side of the house, and so on,” President of OU’s AP Association Marie Vanbuskirk said. “… We are mostly the supervisors of employees on campus and other employee groups. And we are the largest supervisors of student employees on campus. So we talk to the students, and hear from them in many different ways and also guide and advocate for them.”

APs aren’t unionized and don’t bargain with the university, but leadership in the AP association does meet regularly with the administration to discuss working conditions and improvements they would like to see made.

“AP Association [acts] as a liaison for APs to the administration,” Vanbuskirk said. “We present all things … wages or compensation, working conditions, benefits and so on.”

Vanbuskirk says AP Association leadership currently has three top priorities for its members – improving compensation, work/life balance and diversity and inclusion. This year APs saw a 1% salary increase, as well as a $500 lump sum raise.

According to Vanbuskirk, APs are generally happy with their compensation package, though she still sees room for improvement if the university is going to be competitive in attracting and keeping APs.

“There hasn’t been significant merit increases in a long time,” Vanbuskirk said. “So that’s why we are advocating to reconvene the compensation committee so that we can work together to solve this problem … I do think it’s problematic in retaining employees.”

The group on campus with the lowest wages and least amount of agency in the workplace is undergrad student workers. Work-study programs and other work opportunities on campus for students are often great ways for students to network and get experience in their field, and because these jobs are highly coveted the student workers occupying them are often seen as easily replaceable. This is especially true with university housing jobs, as landing the right role with housing means getting thousands of dollars a year toward room and board, a benefit which most students simply can’t afford to lose.

Student Jeremy Johnson has found himself in the middle of multiple disputes between student workers and the university. As an employee of student housing, he and several other students formed the Oakland United Student Workers Coalition (OUSWC) as a way to advocate for better working conditions for students on campus. And as a Legislator for Oakland University’s Student Congress (OUSC) Jeremy Johnson was one of several student workers being denied wages for the hours they were working, a situation that was only rectified after a Legislator strike completely dismantled OUSC’s E-Board and The Post published an article on the controversy.

Last year OUSWC organized, leveraging the possibility of a large student protest outside of Pescovitz’s presidential housing Sunset Terrace, and were successful in saving housing jobs that were going to be cut. For their efforts, the lead OUSWC organizers Jeremy Johnson, Andrew Romano, Jordan Tolbert, Sam Torres and Emily Sines were retaliated against by the university, losing their jobs and thousands of dollars in housing stipends.

“They wanted to silence us,” Jeremy Johnson said. “… We wanted to make OU a better place. We wanted to help our coworkers at the time, and we were punished for doing so.”

Since being fired from his housing position, Jeremy Johnson says he’s essentially been blacklisted from any on-campus job opportunities, with his current employment as Speaker of the Legislature of OUSC only being possible because in the SAFAC orgs students and not professional university employees are in charge of hiring decisions.

As a member of OUSC Jeremy Johnson remains an advocate for improving the conditions for student workers, pushing to reduce the cost of college for students with free textbooks initiatives and OUSC’s “Raise the Wage” campaign. According to Johnson, these efforts have been met with resistance from the university.

“It seems overall like the administration is averse to change and averse to improvement, and has this inability to accept ideas that come from students, or faculty or staff,” Jeremy Johnson said.

In response to OU AAUP’s allegations that the university bargained in bad faith, Jeremy Johnson was concerned not just for faculty, but with what the implications of these allegations would mean for more vulnerable workers on campus.

“We have seen how unwilling this administration is to negotiate with the [AAUP],” Jeremy Johnson said. “And they’re even more harsh against the student workers that they see as disposable. Unlike other workforces on campus, student workers don’t have any union protecting them … They can’t advocate for themselves, but they still depend on these jobs to stay in college. And this results in a coercive work environment where people have no choice but to submit themselves to whatever they’re being told … The administration knows this, and they take advantage of it. For the lives of student workers to improve, they have to be able to advocate for their needs … People need to be able to say what they think is necessary without fear of being destroyed.”

So with these allegations, workers around campus are paying attention to how the university is choosing to respond. To this point there has been no announcement from the administration of a further investigation into the allegations, and the only official correspondence on the allegations was the statement supplied to The Post.

If the university decides to altogether disregard OU AAUP’s letter, the faculty union has a couple different options for insisting the university takes action. They could do a vote of no confidence in President Pescovitz, or they could take the university to court and argue their case that the university violated labor laws and the current contract agreement by bargaining in bad-faith.

A no-confidence vote, while not taken lightly, is mostly just a way for faculty to express dissatisfaction and the university is not required legally to take any major action based on that vote. The last vote of no confidence was against President Gary Russi following 2009’s faculty contract negotiations, and it did not lead to Russi being removed from his position.

To this point, The Post isn’t aware of a major push in the union for a no-confidence vote. A lawsuit, however, is something that has been considered.

“We have discussed this matter with our lawyer,” Miller said. “We are discussing other questions. We are in consultation with other faculty unions in the state. We are in consultation with AAUP National. So we’re deeply concerned and we can’t just pretend this didn’t happen.”

Despite this controversy, OU AAUP leadership remains optimistic that the situation could improve with better communication between the two sides.

“I think there are ways that we can work well together,” Pollard said. “There are ways that the union currently works well together with administration right now. But I think we can do more. That’s what we’re trying to do. And to not have the other side [be] part of the conversation with us is frustrating.”

OU AAUP leadership recognizes the value of shared governance and remains committed to improving the current state of relations between faculty and the upper administration. A lot of faculty frustration following contract negotiations has had to do with their perception that the upper administration and BOT aren’t as committed to that ideal as they are.

The BOT’s recent rejection of an OU AAUP proposal to add two faculty liaisons to the BOT didn’t do anything to dispel the notion that the upper administration isn’t interested in faculty having input on major issues facing the university.

Going forward OU AAUP will continue to push for more communication, transparency and accountability from the administration.

“It’s fair to say we’re not done with the conversation,” Pollard said. “We don’t want to have a conversation through the student newspaper. It would be good to have a conversation with some Oakland leaders … We’re working together on a daily basis. We still move forward, we still function … So there is this act of collaboration. It’s really important to build on that and to not see it as the administration and the AAUP are enemies. There’s certainly work to be done.”

just wondering • Feb 10, 2022 at 5:50 PM

not sure why jeremy johnson got brought up in a AAUP article?

anon • Feb 8, 2022 at 3:06 PM

If BoT and upper admin’s behavior thus far does not constitute pure and unmitigated enmity, then what does? Class A felony?

“… increasingly stronger relationships between faculty and administration…” No, thank you. We’ve had enough of those “relationships” with this clique of shameless, greedy, hypocritical, egotistic, and downright immoral liars.

Annette Gilson • Feb 8, 2022 at 11:58 AM

Standing with OU students. I am dismayed by the treatment Jeremy Johnson and others have received. Great article. Keep paying attention, and thank you for the work you are doing.

J. Man • Feb 8, 2022 at 8:04 AM

OU’s leadership has already lied to the faculty, rejected the option of a faculty liaison, and retaliated against student staff. It is unlikely that this situation will improve.