COLUMN: Ernie Harwell leaves behind legacy of respect

It was 9:30 on an innocent enough Tuesday night, at a cottage in Gaylord, Mich. My attempt to roast marshmallows was foiled by steady rain, rhythmically pinging off of the roof, splattering and rolling down the window.

Sitting at the table waiting for my girlfriend to finish dinner, I checked my phone for the score of the Red Wings’

Game 3 against the San Jose Sharks.

Addicted, I consulted Facebook mobile first. Instead of reading the pending bad news of the hockey game and preempted end to the Wings season, I scrolled through to see expected, but still devastating condolences.

Such as the rain was splattering and rolling down the window, tears began to roll down my cheek, splattering on the screen of my phone.

Ernie Harwell had passed away.

Completely beside myself, I cried in such a way I had not cried since my grandfather passed away seven years ago. Trying to “be a man about it,”

I wiped my face and held in my tears as my girlfriend turned away from the stove to bring my plate.

Picking at my broccoli, all I could hear in my head was his voice. All I could hear on the outside were her attempts to make small talk. There was nothing I could say or think of other than Ernie Harwell.

I remained stone-faced, turned down, every muscle in my face clinched. The slightest movement would be like a bulldozer busting through a dam.

Finally she asked me if I was okay. I slowly looked up. She could see what I was trying to contain; the pain was visible on my face.

I let loose and completely broke down. She hugged me but that couldn’

t do much. She asked me a very valid question; What did he mean to you, to evoke this?

Ernie was a surrogate grandfather to me. He was always there every summer night, from the time I was six until 14. These formative years of my life, were spent in the car or garage with my father, listening to Ernie’

s warm, gentle southern-drawl, tinged with a bit of a lisp, explain everything that was on the field before him, simultaneously painting a picture to project in my young, squishy mind.

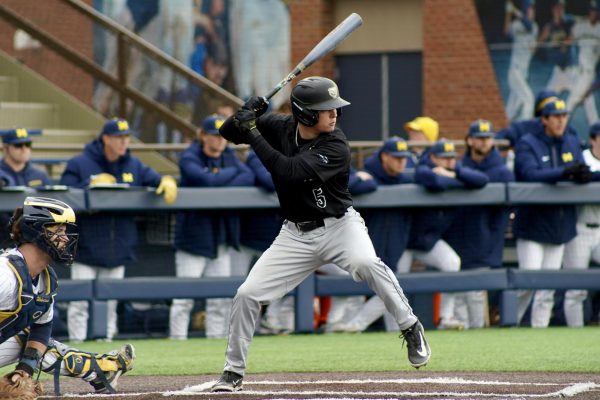

My first hero on the diamond was Cecil Fielder. I always identified with him most because, like myself as a child, he was a fat first baseman.

Upon news of Harwell’s death, I began to think, what if he didn’t make listening to Tigers’ games so inviting? What if Ernie wasn’t there to say, “LOOOOOOOONG GONE!”

every time Cecil bounced one off the left field roof of Tiger Stadium? Would I have gotten that excited every time Fielder came up to bat?

I knew every time he came up to bat there was a good chance Ernie would end up yelling his signature phrase. Maybe Ernie was just my favorite and everyone else was there to serve as actors in the play he was narrating.

This made a big enough impact that around the age of eight, I decided I wanted to be a sports broadcaster.

Hey, if I end up becoming the next Cecil Fielder, cool, but I really want to be the next Ernie Harwell. I wanted to paint the picture in everyone else’

s mind. I wanted to be so powerful that I could enthrall you with just my voice and a bit of ambient sound.

Like Ernie, I wanted to be so natural and personable. It seemed as though you were blind and he was sitting next to you, describing the action as a personal favor, not a job.

On Monday, I went to the Detroit Tigers game against the New York Yankess to, in a sense, pay my final respects. It was the first home game for the Tigers since his passing. Comerica Park went into a moment of silence (through which I heard heathens still conversing).

They began to raise Harwells honorary flag, suddenly the relative quiet broke as they played a clip of audio; scripture “Song of Solomon”

that Harwell would recite at the beginning of every spring training.

“For lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone; the flowers appear on the earth; the time of the singing of birds is come, and the voice of the turtle is heard in our land.”

Upon hearing his voice, a chill was injected into my spine, raced up back, then exploded through out my body. I held my composure one more time, as the audio faded out.

Ernie Harwell liked referencing turtles. In speeches he would often say, “I’m a turtle on a fence post. You know when you see a turtle on a fence post, he didn’t get up there by himself.”

When it comes to Ernie and what he meant to me as a broadcaster and person, I like to think of myself as that turtle on the fence post.

I didn’

t get up there by myself, I got there because listening to him shaped my rabid love for baseball, and my passion to do what he did.

Thank you, Ernie. There is nothing more I can say except, thank you.