In May of 2024, Oakland University administration and Oakland University’s Chapter of the American Association of University Professors (OU-AAUP) will begin faculty contract renegotiations.

In 2021, contract renegotiations were notoriously bitter, leading the faculty to strike at the beginning of the fall semester.

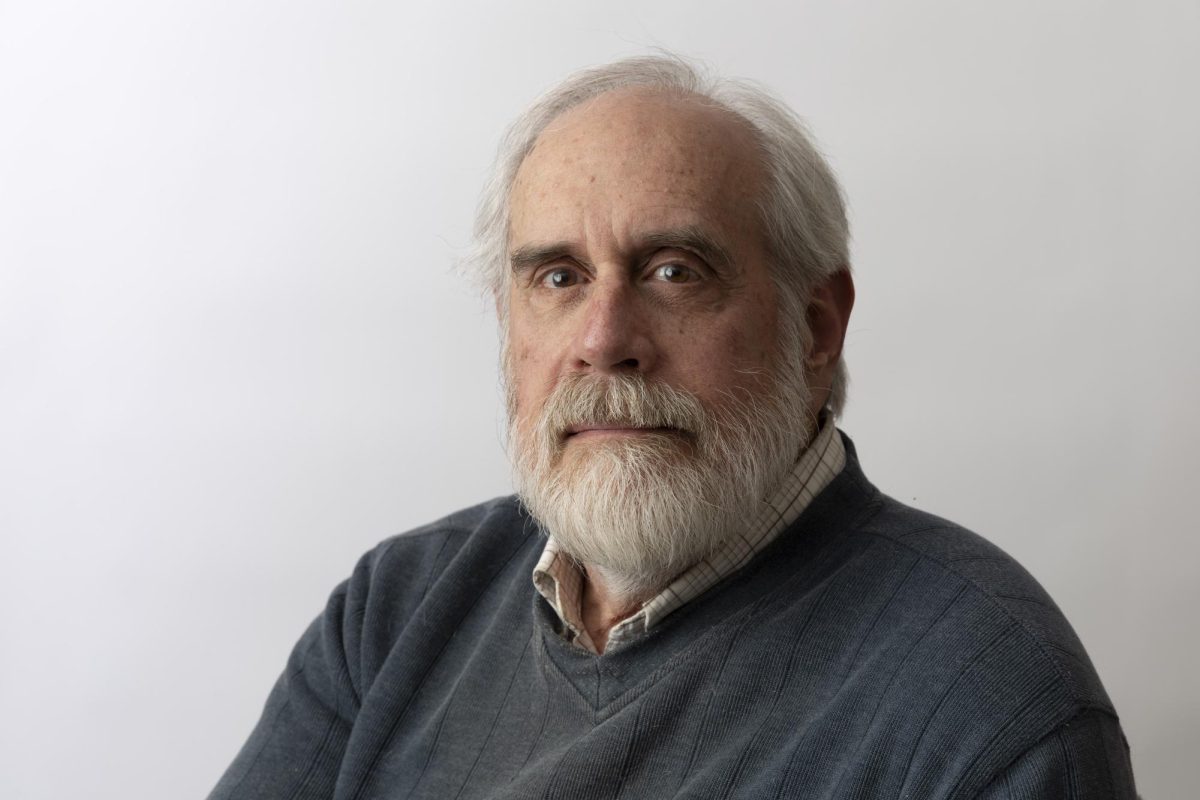

Recently, The Oakland Post sat down with OU-AAUP President Michael Latcha for a conversation on next year’s renegotiations, current faculty sentiment toward administration, and his hopes for the future.

OP: What are your goals as OU-AAUP President?

ML: “Some of the goals have been kind of evolving as I’ve stepped into this role. I’ve never been the president before. I have been the vice president a couple times. I have served on the executive committee for 20 years or so. It’s clear that a lot of the faculty that we have now, especially the newer faculty, they’re not aware of a lot of their rights and their responsibilities in dealing with the administration.

Both of those issues are written down for everyone to read and understand. Not only the faculty agreement but also in the constitution and the bylaws of all of the schools and the colleges. A lot of people don’t seem to understand that those things exist, and they don’t understand the power that gives them. That’s one of the things that I’ve decided to try to do with these two years –– is to make people more aware of that. Show them how they can use this to stick up for their own rights and the rights of other faculty members and to be able to get back to a more shared type of governance on campus.”

OP: What challenges are you currently facing as OU-AAUP President?

ML: “Certainly post-pandemic, there are issues on campus that we’re going to have to work with the administration on. It’s no secret that the student body is three-quarters of what it was. That transition, and hopefully building up the student body is going to take some serious conversation to make sure that all of that is not just one-sided.”

OP: Currently, what is the sentiment from the faculty toward the administration?

ML: “The morale of the faculty has not greatly improved since the fall of 2021. We know that going in, and the president knows that also. She has been told that several times and in several different ways. That’s not a surprise on either side. We have surveyed the faculty, we have gotten over 500 responses to the survey that we sent out to faculty, and we are sifting through those looking for issues, priorities, things like that. Those will be those will eventually be turned over to the burdens to develop their strategies.”

OP: What issues have stood out to you while conducting this survey?

ML: “People are not happy. Kinda across the board not happy. Certainly, money is a huge issue. We have not had a significant raise for seven or eight years –– before 2021. It’s going to get worse in January since the amount that the university will be contributing to healthcare is going to decrease, so we will end up having to pay more for that.”

OP: How do you hope that OU administration responds to the concerns of the faculty?

ML: “There’s a lot of things that I could hope that they do. The big thing that I would hope that they do is to actually sit down across the table and talk to us. That has not happened in over 10 years. Oakland insists on hiring outside attorneys to do their renegotiations. I have mentioned this to the president. She thanked me for my input.”

OP: For those who are unaware, can you describe what challenges OU-AAUP faced during the contract renegotiation process in 2021?

ML: “In 2021, the administration pretty much looked to gut everything out of the agreement. So we have a fairly, you could say, generous tuition waiver system, and ours is very different than the way it is at most schools. The way ours was set up back in the 1960s is that if my dependent wanted to take a class at Oakland, the course cap for that course would be increased by one, which means that it costs Oakland no money. That’s very different than the way it is at the vast majority of schools. At most schools, that person is actually counted as a student in class. At Oakland, it’s not, and the way it was structured is that we, the faculty, teach other faculty dependents for free. Oakland does not see it that way. They see another body in class as ‘lost tuition’ even though structurally, they’re losing nothing. So when they went after the tuition benefit, that got a lot of people very upset.

Another thing that they went after in 2021 was our retirement benefits. We don’t have a pension, so Oakland makes contributions to our retirement accounts. If you look at the number, you would say that was very generous. However, the reason that number is so high is because, in the 1980s, when inflation was running at double digits –– it was running 12-15% a year. When we were only able to secure raises in the 6-8% range. Oakland at that point was offering more money into the retirement accounts, figuring that they would not have to pay for that for a while. So that high number that we have in 2021 –– that was bought and paid for in previous contracts.

For people who’ve been here for more than two years, it was 16%, and Oakland was looking to reduce that to what they considered a more normal amount of 10% but without actually paying for it. The way that got settled was sort of a two-tier system. People that were hired after 2001 got 10%, the rest of us who have been here longer stayed with the system. It really didn’t save Oakland anything except in the very long run.

They had no money on the table essentially until the very end. Any money they had on the table was only for merit. There were no across-the-board raises or anything else. Then the last big piece was healthcare. They were looking to move that to decrease their contribution much sooner. All of those things taken together, they sort of sum up a lack of respect. Then of course immediately as soon as the fall semester ended in 2021, inflation skyrocketed, and anything that was in the contract just evaporated. It was gone in the winter of 2022.”

OP: How are contract negotiations different now from in the past?

ML: “The main difference that we see is we do not speak to the administration. We speak to someone who is not an academic, who does not have to administer the contract, and who does not have to live under its rules. We’re still not quite sure who that person takes their orders from to go to the table. It used to be that we sat down with people, for instance, from the Provost office. Everyone that was at the table lived and worked and breathed Oakland. So we were able to talk about issues that we all knew were issues because we live them every single day. We were able to come to either an agreement to disagree or more often, we worked out solutions that everybody bought into right there at the table.

[That] doesn’t happen anymore. It has not happened since 2012. So that is what I think is seriously missing from contract negotiations. I’ve seen it both ways. It was much more collegial before. Not to say that either side didn’t bargain very hard because we all did, [but] you bargained with the singular idea that we could make Oakland better.”

OP: What are you hearing from the OU administration at present?

ML: “I regularly speak with many people in the administration. The people that would be involved with making decisions with bargaining have told me that I will be pleasantly surprised. Don’t know what that means, but we’ll see what happens.”

OP: What do you see as the best possible outcome for contract renegotiations next spring?

ML: “I absolutely would like to see the faculty and the administration working closer together. That would be the very best outcome I think, because right now we do not. I don’t think the faculty trusts many people in administration, and because of that, faculty have pulled back from interacting with administration. That’s not healthy. That’s not the way a healthy university works. If we can change that, then that would be fabulous.”

Suspicious prof • Dec 6, 2023 at 2:23 PM

With all due respect to Prof. Latcha, the interview is somewhat amorphous and hardly hopeful.