Letter to the editor: A Personal Take on the Changing Landscape of OU Contract Negotiations

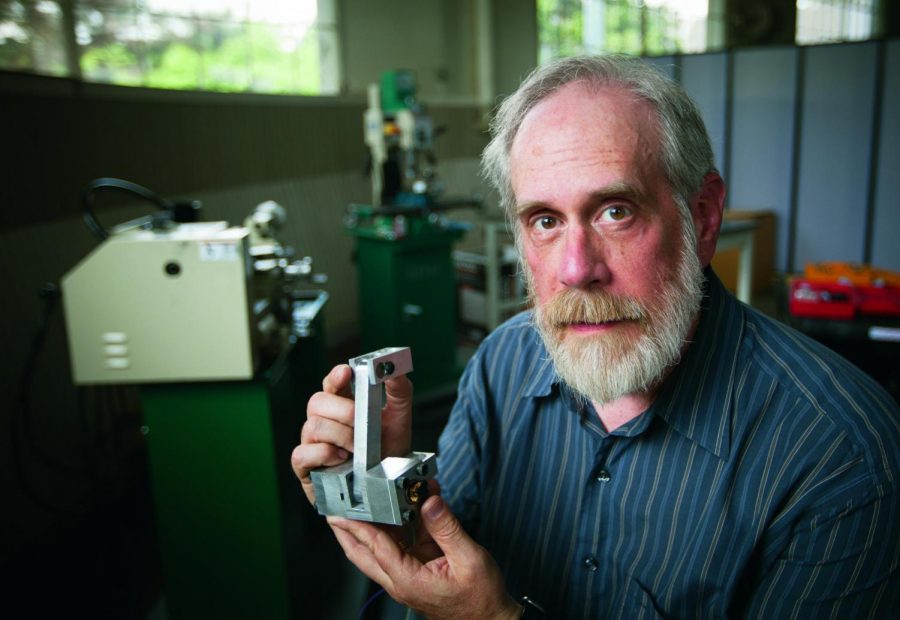

Photo courtesy of Crainsdetroit.com.

Oakland University Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Michael Latcha.

I have been fortunate to have served as a member of the AAUP bargaining teams in 1994, 1997, 2000, and then as chief negotiator for the AAUP in 2006, 2009, 2012 and 2015. During this time, I’ve witnessed fundamental changes in the landscape, attitudes, and outcomes of negotiating at Oakland University.

For most of my bargaining history, contracts were negotiated between OU administrators and OU faculty. Each side would pick a team of people very familiar with the issues, folks that worked with the issues, and each other, day to day. Negotiations were highly contested, with each side advocating strongly for what they believed was better for faculty, students, and the university. Bargaining points were made and countered by both sides with an intimate understanding of the processes and procedures that made Oakland University work. When focused on a particular point, often the very people that would be most greatly impacted by the discussion would be invited to talk with the bargaining teams, to avoid unintended and unfortunate consequences. Moreover, everyone on both sides of the table knew that once a settlement was reached the job of administering the Agreement and making it work would fall to them, and their main allies in that task were the folks sitting across the negotiating table.

In 2000 then-president Russi wanted to try a less contentious method of negotiating, namely interest-based bargaining. Interest-based bargaining focuses on desired outcomes and needs, not positions, and relies heavily on the open and honest flow of information between the two sides. Oakland hired an outside attorney to co-chair their team who was known as an expert in this style of bargaining, and both teams went through training sessions to become familiar with the process.

Even though a settlement was reached in record time and with what looked like surprisingly good results on both sides, it was ultimately tainted when it was discovered that Oakland withheld vital information concerning sabbatical denials and health-care rates from their team. This underhanded maneuver effectively ended the prospect of ever again using interest-based bargaining at Oakland.

The same outside attorney was re-hired by Oakland in 2003, this time armed with a scorched-earth agenda, much to the horror of the Oakland administrators that filled out their team. The AAUP team had to fight valiantly just to eke out a settlement without giving up basic provisions and protections.

The summer of 2006 found Oakland administrators again leading their team. Notable in 2006 was Oakland insisting that all unions on campus be stripped of any retirement health benefits, a benefit just recently won by the faculty in 2000. While the original benefit was kept by faculty who were close to retirement, the remainder of the full-time faculty had the choice to keep a reduced benefit or an increased retirement contribution. Both sides knew during bargaining that these choices would be difficult to administer, and they continue to be challenging today. However, the people who would administer the provision were the very people who negotiated it, and remain committed to providing the benefit as it was negotiated and adopted.

In 2009 Oakland administrators again led Oakland’s team, with the pressing need to incorporate the planned medical school into every part of campus. Negotiations ran very hot as Oakland refused to share their vision of how the medical school was to operate, ultimately leading the AAUP to write it out of the Faculty Agreement (which was probably Oakland’s intent all along). Oakland also took aim on faculty intellectual property (a provision that the two 2009 chief negotiators co-wrote in 1994, and one that remains a model for AAUP chapters across the country) and attempted to void a MERC ruling on an unfair labor practice suit chastising the OU president for repeatedly violating the shared governance provisions of the Faculty Agreement. Lack of a settlement by the first day of class led to the AAUP team asking the faculty to withhold their services, which was followed immediately by a very early morning visit to the Oakland County courthouse the next day. With the blessing of a surprisingly sympathetic judge, negotiations continued in non-stop marathon sessions for several more days while the faculty continued to withhold services, ultimately coming to a settlement. This would be the last time the faculty would have the opportunity to negotiate directly with Oakland.

In 2012 and 2015 Oakland hired a local attorney to lead their team, an individual with a long history of negotiating for employers against unionized employees. This very high-priced individual, who often confused the many negotiations he was juggling, regularly came into bargaining sessions with proposals that attacked the foundations of the relationship between Oakland and the faculty, often to the clear surprise and shock of the Oakland administrators sitting next to him. Any more than a brief introduction revealed this outside attorney knew nothing of Oakland, its history or how the university functioned day-to-day. Armed with an aggressive agenda, his simple task was to try to reduce faculty pay, seek more control over faculty raises and promotions, slash health insurance and tuition waiver benefits, and even repeatedly attempt to alter the very definition of the faculty bargaining unit, while denying all requests from the faculty team. Seldom were the other members of the Oakland team even allowed to speak. There was no collaboration in sight, only conflict.

With the passing of right-to-work legislation in Michigan at the end of 2012, the ground shifted even farther in the direction of employers. That legislation meant that Oakland, as an employer, can ultimately dictate the terms of a contract in the event negotiations break down. Because of this power there are few reasons for Oakland to enter a meaningful negotiation with the faculty. There is little motivation for Oakland to compromise, which makes it easy for the administration to ignore that bargaining with the faulty is an opportunity for productive and cooperative discussion. Oakland has demonstrated time and again that it is content to hide behind hired outsiders to force their agenda on the faculty while simply running out the negotiating clock. No meaningful, collaborative negotiations between the administration and faculty have occurred in a very long time. We saw the results of these divisive strategies in 2021 when this same high-priced attorney again led Oakland’s team, with now-predictable outcomes at the end of negotiations, and the administration’s subsequent retaliatory lawsuit accusing the faculty of (gasp!) going on strike.

Perhaps someday OU will once again have thoughtful and collaborative administrators, who are not afraid to talk to and negotiate directly with the faculty, a faculty who seek to collaborate in problem-solving and moving the university forward. This hope should be the faculty’s focus as we continue to work for a better university. The OU faculty need to use our biggest strength – our solidarity – and take every opportunity to provide feedback, input, and counsel. Stand together and do not lose the chance or the ability to suggest, advise and even build wherever administrative leadership lacks. Participate fully, especially when administrators are sought and hired. By working together as one faculty, we can overcome the shortsightedness and divisiveness of the administration and make Oakland University a better place to learn, grow and cooperate.

Theresa Rowe • Apr 15, 2022 at 7:39 AM

The fear to talk openly, to negotiate directly, and to openly share facts and information is pervasive in the administrative culture. For years, the faculty union provided valid input to a check-and-balance system with the administration. But hidden agendas and information have taken over. Even a comment here is signed Anonymous, which is telling about the culture. You’ve described the situation well. It affects more than faculty negotiations. Thank you for providing the history.

Nigel Harrington • Apr 16, 2022 at 12:02 AM

Thank you Mike for this wonderful writeup about the history and changing culture at Oakland. I am disgusted that Oakland continues to hire this Robert Boonian who knows nothing of Oakland our culture or our values. It’s shameful that OU continues to hire this guy to negotiate on their behalf which tells me that they fully support his vision, values and the payouts he negotiates. It’s painfully clear that OU does not see the faculty or our wonderful students as assets. They think of the faculty as a cost and our students as credit hour generators. We need to fight back and get rid of these administrators. Take back our university.

Ora, do you hear the people sing? Singing the song of angry men?

Anon • Apr 16, 2022 at 2:35 AM

Ora does not give a crap. Invoking her conscience is pointless, for there is nothing to invoke. These angry men can sing a two-hour oratorio to the same effect of nothing. The failure to get enough momentum for the no-confidence vote illustrates our faculty’s resolve (rather, the lack thereof) to fight back. The whole system of “governance” is designed to give us zero leverage on this caste of narcissistic mediocrities who, in their delusional thinking, believe they are “academic leaders” while being neither academic nor leaders.

Anonymous • Apr 14, 2022 at 6:49 PM

In this last negotiation, the position of the OU bargaining team was absurd, regressive, and disrespectful. The contract we were presented with will do long lasting damage to the university by making significant cuts in areas critical to student education. Students should know that they were kneecapped by this contract, too.

When we walked out, the students supported us, staff supported us, even the police and fire department who would drive by and waive supported us. It was a sight to see. But then you caved. You accepted the idea that you really didn’t have options. You didn’t even have a protest on Labor Day, for god’s sake. You didn’t even try to test the idea that we could vote no and go back to the bargaining table. You told all of the members that if we voted no we would have an even worse contract immediately imposed on us with no recourse. You caved. You gave in. Capitulated. Get a thesaurus, because we need more words to describe it.

Personally, when I say that I hope to have new leadership in place by the next contract, I mean in both the OU administration and the AAUP.