Local advocate Ashley Rapp works to end period poverty

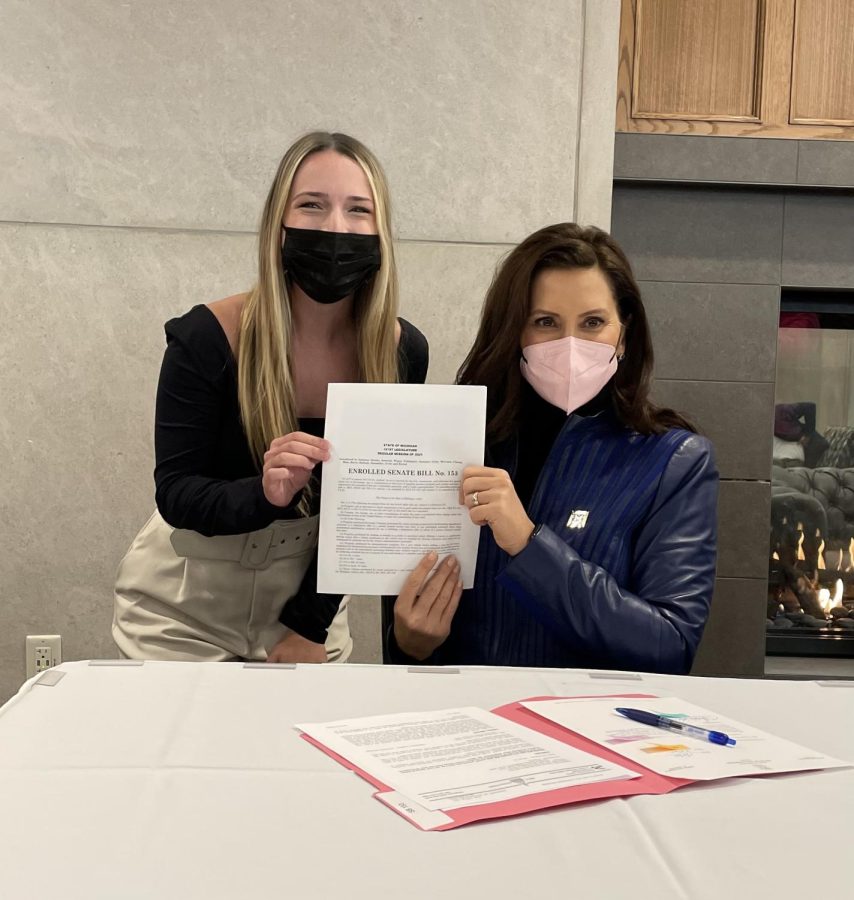

Rapp poses with Governor Whitmer holding the bill to end the period tax.

Epidemiologist, Miss Michigan 2021 candidate and menstruation enthusiast Ashley Rapp has been working toward ending period poverty — inadequate access to menstrual hygiene products — since she was an undergraduate at Grand Valley State University (GVSU).

The Sterling Heights native started hosting period product drives at school to donate to the GVSU food pantry before taking her drives to the metro-Detroit area. As a Chaldean woman, Rapp has a passion for making sure that menstruators in the Middle Eastern community have access to products. One year for her birthday, she asked only for period products and collected thousands that she was able to give directly to members of her community.

Through her drives, Rapp realized just how many groups need help and that the issue of period poverty is systemic. She decided to get involved in the legislative side of handling period poverty, and a big step in her mission was ending the tampon tax.

The tampon tax is the 6% sales tax on menstrual products such as tampons, pads and similar products, which are deemed as non-essential, luxury items. Menstruators in Michigan pay about $7 million in tampon taxes a year, according to Bridge Michigan.

On Friday, Nov. 5, Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed the second of two nonpartisan bills — HB 4270 and HB 5267 — that will eliminate the tampon tax in Michigan and recognize menstrual products as essential goods.

The process, though, was no easy feat. According to Rapp, people in the Michigan legislature have been trying to get the tampon tax eliminated since 2017. The bill was initially developed by women of color, Rep. Tenisha Yancey and Rep. Padma Kuppa.

“In 2019, Representative Tenisha Yancey, who was one of the original sponsors of the bill, reintroduced this bill into the House,” Rapp says. “What she was really excited about was getting the people who had worked on this advocacy in front of the tax policy committee, so she actually called a couple youth activists that she knew.”

One of those activists was Rapp, who, young and nervous, stood up in front of the House finance committee and gave an oral testimony. The bill, however, died in committee before anyone could vote on it.

The bill’s failure in 2019, though, did not discourage Rapp or her fellow grassroots organizers and young activists. On Oct. 6, period equity advocates gathered at the Michigan State Capitol for Michigan Period Action Day where Rapp had another opportunity to speak.

In the summer of 2021, Rapp also had the opportunity to spread her message of ending period poverty to an even larger platform: the Miss Michigan pageant.

“It was not something I ever expected to do, but for me, looking back it really showed that advocacy can look a lot of different ways, and there’s not a cookie cutter way to approach activism,” Rapp says.

Advocacy exists in small efforts, too. A stigma around menstruation exists that leads to hesitancy in discussions about the topic. The first step, Rapp explains, is starting the dialogue.

Rapp says: “If we don’t talk about periods and pads and tampons or anything in that vein, nobody will know about it, and nobody will be able to help us take action and make change. I think that, honestly, talking about things is advocacy and activism in its own small way.”

Rapp’s advocacy will continue beyond the success of Michigan’s tampon tax bill — which she calls a “drop in the bucket” in the progress of ending period poverty.

“Eliminating the sales tax on menstrual products does a little bit to make them more accessible, does a little bit to make periods less stigmatized, but it doesn’t do enough — more needs to be done,” Rapp says. “In my mind, the next natural step is to make products freely available in public schools.”

Mike • Dec 15, 2021 at 2:37 PM

I am not opposed at all to the sentiment of the woman mentioned in the article but the Post needs to educate their editors on biology. The substitution of women or woman with “menstruators” is the product of leftist mental programming. Despite what woke leftists say the only people in all history to have a period are women.