The worst faculty contract negotiations in OU’s history: How did we get here?

Photo courtesy of Oakland University

Three months of negotiations, three deadline extensions, three days until the start of the fall semester and there still isn’t an agreement on the table between the administration and OU’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors (OU AAUP). A mediator from the Michigan Employment Relations Commission will be joining bargaining sessions this week, but, with both sides far apart on key issues and the midnight Aug. 31 deadline looming, the start of classes Thursday is in jeopardy. So, how did we get here?

Well, this starts back in the summer of 2020 when due to the unprecedented circumstances of COVID-19, an agreement was reached to extend the prior contract one year to midnight Aug. 14, 2021. In what now seems an inconceivable show of unity between the administration and faculty, the two sides came together so OU could weather the storm.

“[Last year] we and the administration wanted to spend all of our energy doing the best we could in terms of figuring out how to make the university functional during [COVID-19],” President of the OU chapter of the AAUP and Associate Professor of History Karen Miller said. “We were satisfied with the old contract in the sense that there were things that we disagreed with, and I’m sure there were things that the administration wanted to change, but they really paled in comparison to the larger concern — the immediacy of [COVID-19].”

Fast forward to May 2021 when this current round of negotiations began. Discussions between the two sides started in an amicable enough way. A baseline for negotiations was established throughout June, with both sides agreeing to 18 articles from the prior contract being placed into the new agreement.

From that initial point of agreement, the two sides presented concerns on non-economic issues like faculty wanting updated language concerning pronouns and expansion of groups protected from discrimination. The recurring theme between the two sides during this period was the AAUP wanting increased specificity in the language of the agreement and the administration working toward “eliminating some undue complexities.”

Events at the end of June and beginning of July showed the first sign of friction in negotiations. This was mainly due to the Board of Trustees (BOT) approving a new budget and increased tuition. OU AAUP specifically criticized a single-year expenditure in the budget of $6,942,893 to replenish the university’s reserve funds, saying “It is our understanding that the decision to return this full amount to reserves in a single year, rather than using it for current needs, constitutes just that, a choice made by Oakland.”

The next major development occurred on July 22, when OU AAUP put their first major economic package on the table. Among other things, it brought forth specific proposals like a 3.5% increase in salaries, paid parental leave, increased research fellowships and better benefits for special lecturers.

The administration chose not to respond to this package until two weeks later on Aug. 5. That day proved to be the turning point in the tone of these negotiations, as the administration’s package was so far removed from the union’s that faculty were left shocked and insulted by the proposals that had been put on the table.

“There were things that the other side put across the table that we thought ‘Oh, come on. This is silly,’” Miller said. “… We started getting to financial conversations … the nitty gritty … What are the health care costs going to be? Is there going to be a dental plan? … As soon as we started talking about that stuff across the table, very quickly, people got angrier and angrier. You know, they’re not saying anything about cutting retirement benefits for administrators. They’re not talking about cutting retirement benefits for deans, they’re talking about cutting retirement benefits for faculty. And that makes faculty angry just to bring that to the table. And especially because we still are fairly confident that we don’t get paid, as well as people at other institutions.”

The issue of “market adjustments,” or making sure the salaries of OU professors are competitive with comparable institutions, has been a major issue for OU AAUP. The union provides anecdotal evidence that OU faculty are underpaid, and has been trying for years to bridge the salary gap between OU faculty and professors at comparable universities. The administration’s proposal made it clear that no market adjustments would be made.

The aforementioned cut to benefits in the administration’s proposal included a reduction from 14% to 10% in the university’s contribution to faculty retirement plans, as well as removing dental and optical insurance and increasing the employee contribution to the health insurance plan from its current 5% to 10% in the first year of the new agreement, 15% in the second year of the agreement and 20% in the third year of the agreement — while allowing the administration to make changes to healthcare plans not mandated by providers.

Among other things, the proposals also froze minimum salary at current levels for the length of the agreement, froze the amount allocated to research and travel for the length of the agreement, included no or minimal raises of $500 for full-time faculty in the first year and then a 1% merit based increase for each subsequent year, changed the rate of pay for summer instruction from the salary based system to a flat per-credit-hour rate, eliminated faculty choice in online-instruction and gave the administration sole control over retirement plan provider choices.

The administration has moved on some of these positions since their initial proposal, but the fact that they were proposed in the first place was not only detrimental to negotiations, but significantly damaging to the faculty’s perception of university leadership. To fully understand faculty frustration and their position, a little context is in order.

For comparison’s sake, let’s take a look back at 2009. That year the last “worst faculty contract negotiations in OU’s history” took place, when the start of the fall semester was pushed back over a week until an agreement was reached. Some important similarities between that year and now include tremendous economic hardship (2008 financial crisis then, and COVID-19 now) and administrators proposing cuts to faculty pay and benefits after acquiring raises for themselves (President Gary Russi’s $100,000 raise then, President Pescovitz’s reinstating her salary to pre-COVID-19 numbers after taking a 20% cut in 2020 now.) The pivotal difference, and why the administration’s proposed economic package was such a hard pill to swallow in 2021, is the way faculty viewed OU leadership at the time.

Going into the 2009 negotiations, the faculty and administration already had a contentious relationship. President Russi was not necessarily well-liked or respected by faculty. President Pescovitz on the other hand, was for the most part until that Aug. 5 proposal came across the table.

Going into negotiations in 2021, faculty and the administration had just wrapped up over a year of working closely together to navigate COVID-19 and keep the university running. Faculty were not only cooperative, many even lauded the university’s decision making and President Pescovitz’s leadership through the 2020-2021 school year. The Aug. 5 package ruined whatever good faith had been established during the school year, and was received by faculty as a slap in the face.

Adding to faculty discontent was the Aug. 12 announcement that Robert Schostak would be taking over as new Chair of the Board of Trustees. Schostak is a former Republican party chair and was one of the architects of the anti-union right to work legislation former MI Governor Rick Snyder passed in 2012. Speculation about his impact on these negotiations as Chair is a common talking point among faculty.

Shortly following the BOT electing Schostak as Chair, faculty members began going public, expressing their frustrations on social media and through editorials published in The Oakland Post. Generally, those editorials argue the path the administration is taking during negotiations will hurt students, faculty and the long-term wellbeing of the university.

“In this current bargaining year, the administration is playing hard ball, insulting and devaluing the work that I and my colleagues do with proposals that would cut our compensation and drastically reduce our role in decision-making about the academic affairs of the university. What’s even worse—tuition and administrative costs have been rising every year since I’ve been here at OU,” Associate Professor of English & Creative Writing Annette Gilson said.

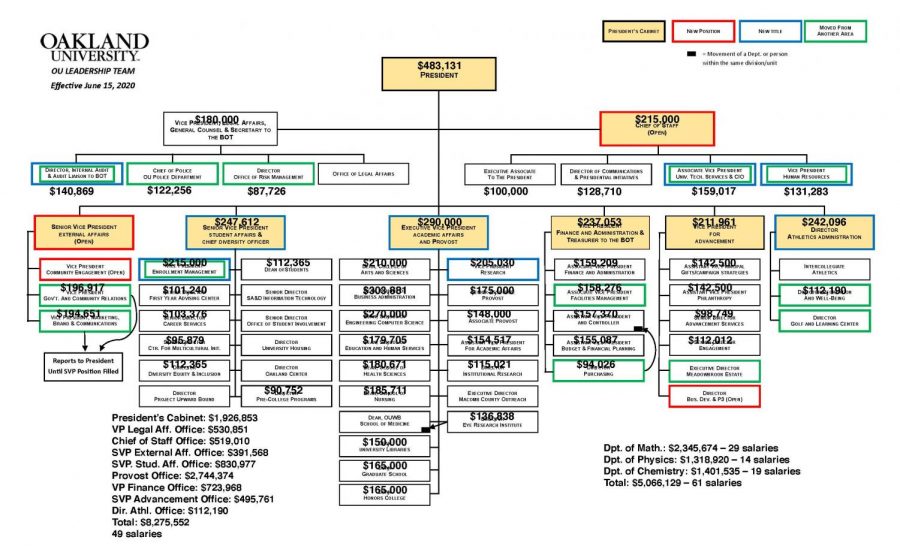

Faculty continue to point toward administrative spending and salaries as an example of the administration’s priorities and proof that money exists for a more faculty-friendly economic package. The graphic included with this article breaks down salary numbers by position based on the information available through OU’s transparency reporting at the following link: https://oakland.edu/Assets/Oakland/Transparency/2021-22/2021%202d_GF%20positions%20by%20title.pdf

The administration on the other hand, has been tight-lipped for the duration of negotiations — declining interviews while negotiations are ongoing and providing only a few updates via the office of the provost. This lack of transparency has added to faculty discontent, as the goals of the administration in these negotiations have been unclear.

“I have no idea what their endgame is,” Miller said. “ … We have made suggestions, in part designed to see what exactly they seem to want. Because it’s hard to kind of figure some of it other than, you know, they want to cut our compensation package significantly.”

And so we have arrived at this point in the negotiations where both the administration and faculty union are steadfast in their positions. The faculty argue they stepped up to the plate last year and deserved to be fairly compensated for those efforts. The administration justifies their conservative economic package by saying the pandemic has hurt OU’s bottom line. The two sides remain far apart on key issues including faculty benefits, salaries, pay for special lecturers and processes for hiring/firing.

Naturally, the faculty are dubious of what the administration says. The question for many has become whether COVID-19 is the reason for the administration’s hard stance in these negotiations or an excuse for it. Doubts about the administration’s intentions were not in any way assuaged when, after agreeing to a six-day deadline extension, they decided to spend five of those six days away from the bargaining table.

Using economic hardship, specifically COVID-19, to try and break a union is not an unprecedented occurrence. Faculty at Western Michigan and Wayne State are currently embattled in struggles similar to their OU counterparts. Almost as soon as the pandemic started, American universities began going after faculty tenure. Around the country, universities are ditching shared governance in favor of short-term self-preservation.

The reality is, faculty don’t have a ton of leverage in these situations. This reality is why OU AAUP members have been so outspoken about their belief that OU is damaging students now and the university long term. It’s why they haven’t been shy in their criticism that the administration’s public message about appreciating professors and doing what’s best for students has not matched their behavior at the bargaining table, or in sharing that they’re mad as hell about what’s going on.

“I am hearing extraordinary anger from faculty members about just an enormous list of things,” Miller said. “Every time we are in the process of changing our faculty contract … Those years are almost always a little more tense than normal. But between the return to campus with COVID [and the] fairly difficult negotiations over the contract, this is really worse than any beginning of the semester I have ever experienced period.”

2020 and 2021 have not been ordinary years for the campus community, the faculty or the administration, these negotiations reflect that. Whether it happens Thursday or in the coming weeks, a faculty contract will be signed and the fall semester will begin. That much we know. What is unclear is the impact of the damage that’s been done to the relationship between the faculty and administration, and what long-lasting effects the outcome of these negotiations will have on the university.

Bargaining will resume Tuesday, Aug. 31.

Sharon Ruthenberg • Sep 1, 2021 at 10:13 AM

Thank you for this summary of the current faculty and administration negotiations.

I also admired President Pescovitz’s leadership when the pandemic first descended.

I’m truly disheartened to learn of the suggested changes in faculty compensation and in medical, vision, and dental coverage. Yet, none of the suggested changes would affect the administration’s executive package.

This demonstrates a complete lack of solidarity and inhumanity

Dr. Sharon Ruthenberg

Fed-up faculty • Aug 31, 2021 at 4:12 PM

“As President Pescovitz said in her letter last week, we may encounter disagreements and differences, but we must always demonstrate compassion, empathy, and understanding.” (Provost Ellis-Rios, Urbi et orbi)

I have a controversial, heterodox, and almost heretical suggestion. How about the Cabinet members, our acclaimed academic leaders, try to lead by example, maybe every once in a while, rather than regurgitate nauseating platitudes?

Anonymous • Aug 31, 2021 at 12:30 PM

“Oakland was prepared to meet late yesterday (Wednesday), last night and today (Thursday), but the AAUP preferred to wait until next Tuesday,” said Joi Cunningham, assistant vice president for academic human resources OU, last week in a statement. “The AAUP has not indicated any intent to engage in an illegal job action or strike, nor has it indicated a need or desire to seek the assistance of the state mediator as a means to resolve the remaining issues.” (From here: https://www.theoaklandpress.com/2021/08/31/potential-labor-strike-at-ou-looms-as-contract-is-set-to-expire-tuesday/)

So, is it Cunningham’s brazen lie?

[email protected] • Aug 31, 2021 at 12:22 AM

Compliments to Jeff Thomas and his team at the Oakland Post, as well as to the faculty who have taught and advised them. Well written and researched!

Barry S. Winkler • Aug 30, 2021 at 8:44 PM

I came to OU’s Eye Research Institute in 1971, the same year the OU AAUP faculty union was established. Reading Karen Miller’s words describing these negotiations as the worst in her decades on the campus, saddens me, despite the fact that during my years on campus (retired in 2012) the faculty struck multiple times to obtain fair contracts. Personally, as a young idealistic Ph.D starting out in the ‘70’s, it took me only two contract negotiations and two strikes to realize I was an employee and not something special in the eyes of the administration. That “special” feeling came from my research, students, and service, just as it does for all dedicated faculty members. Stay the course to achieve a good outcome.

Holly Shreve Gilbert • Aug 30, 2021 at 3:36 PM

Thanks for this excellent synthesis, Jeff Thomas.

The OU Leadership Team chart is especially illuminating. But beyond the executive salaries, there are also nice benefits. A link to the current OU executive benefit package follows.

For those who are interested, highlights include a 90% employer contribution to medical insurance, a $750 per month vehicle stipend, and Medicare complimentary coverage. These are in addition to retirement contributions and tuition waivers – the same benefits that they want to slash for faculty.

Like many of my colleagues I view teaching as a way of life, not just a job. For 27 years I have poured myself into my work, not to mention poured a lot of the modest income I make BACK into the university via the All University Fund Drive and the endowment of a scholarship. The realization of how little the administration values our contributions is demoralizing.

Also, in the interest and credibility and integrity, I encourage everyone who posts to use your name.

Here’s the link to the executive package (you’ll need to copy and paste):

https://oakland.edu/Assets/Oakland/uhr/files-and-documents/2021-Benefits/BenefitSummaries-2021/Executive%20Employees%20Benefit%20Summary.pdf

Tammy Stewart • Aug 30, 2021 at 2:43 PM

Wonderful Journalism Jeff!!!! It’s so refreshing to read the excellent coverage in a student driven paper! I find myself rushing in the morning to login and read the Oakland Post! You folks just rock! So proud to be part of the OU community! This is what OU Admin does not seem to understand!

#Solidarity

J.C. Franks • Aug 30, 2021 at 2:29 PM

As an emeritus faculty member of Western MI University, I can tell you a couple things about this issue are certainties.

First, that this is blatant union busting. Second, that it will be successful both at OU and at WMU. And third, that the quality of education will continue to drop as the entire college and university education system in this country implodes and collapses. It is an economic bubble several times larger than the housing bubble ever was, and it is only now starting to show the cracks of imminent collapse. University boards all know this. The administrations all know this. And the faculties for the most part know it as well.

The students do not, nor do most of their parents, however. Unlike the housing bubble, most parents do not send their children to college with the intention of selling the education at a profit in a year. Education is a long term investment, and in a bubble that is extremely risky.

Anonymous • Aug 30, 2021 at 12:53 PM

Concerning tenure: the changes the OU administration proposes include laying off anybody for any reason and post-tenure reviews. You don’t need to be Albert Einstein and Erwin Schrödinger at once to recognize the process of dismantling tenure.

Cody E. • Aug 30, 2021 at 12:32 PM

Excellent journalism, Jeff. Bravo.

Anonymous • Aug 30, 2021 at 12:15 PM

To be fair: what seems like a $97k raise for President Pescovitz is not a raise if we take the reports for what they are. The President’s salary went from $483k in the 2020 report to $386k in 2021. It is consistent with a 20% Dr. Pescovitz had announced before the previous faculty contract was extended for one year due to the pandemic. The latest report gives back the $483 value, which is the salary she had already had. This is consistent with that reduction being temporary. I doubt, however, that the 20% cut did result in a $97k reduction in the first place as it was relatively short-lived.

Annette Gilson • Aug 30, 2021 at 12:06 PM

Thank you, Jeff Thomas, for your brilliant and thoughtful engagement and support. We are lucky to have students like you in our corner. You are why we do this. Solidarity.