OU Professor leads research on Swimmer’s Itch

Photo courtesy of the Center for Disease Control

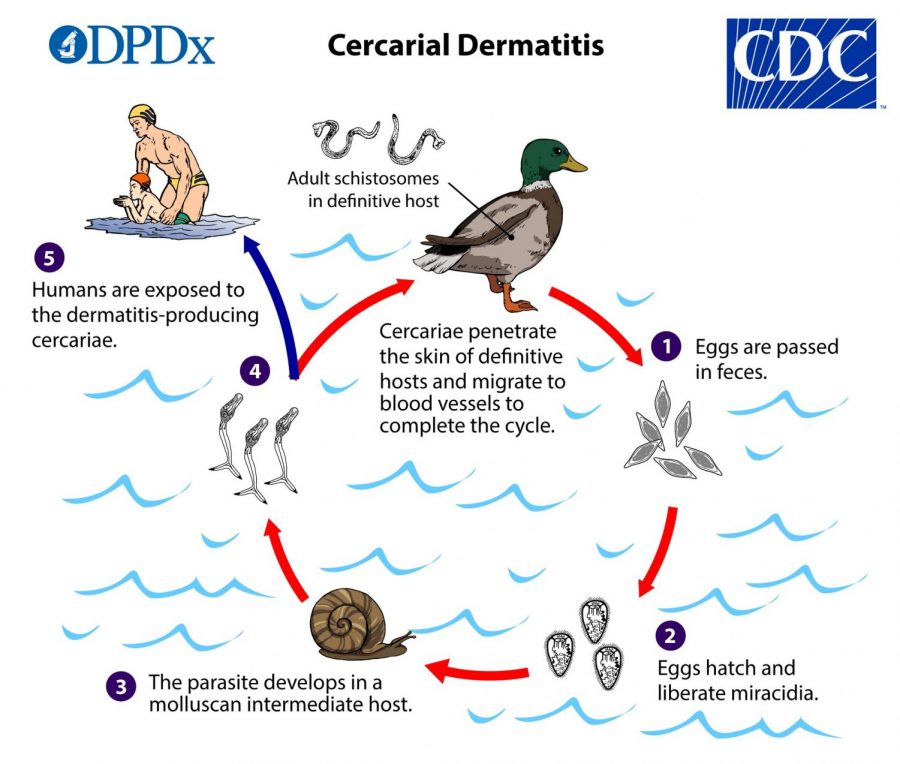

The CDC graphic for the cycle of Swimmer’s Itch.

Picture this: You’ve spent the day swimming in one of Michigan’s many lakes. After a while, you notice red, itchy blisters forming on your legs. What are these blisters? How did this happen?

The red, itchy blisters form a rash called cercarial dermatitis, colloquially referred to as Swimmer’s Itch and are caused by parasitic activity in the water. Cercariae of certain species of schistosomes (larval form of a parasite that requires two hosts to complete its life cycle) penetrate the skin and enter the blood vessels of waterfowl.

Parasitic eggs located in the feces of the waterfowl are then released into the water that hatch into miracidia that develop in their intermediate hosts, snails, before producing the cercariae that infect the parasite’s second host, waterfowl. Sometimes, the parasite may attempt to penetrate the blood vessels of an unviable second host: humans. The parasite burrows in human skin, causing the rash, but it cannot survive in humans and advance in its life cycle.

These parasites “like to move towards light up towards the surface of the water which is where ducks and geese would be floating and swimming, and they are trying to infect a bird,” Dr. Thomas Raffel, an associate professor at Oakland University, said. “They [the parasites] can’t complete their life cycle in a person, but they’ll still try to penetrate our skin which is the mechanism of infection causing the Swimmer’s Itch.”

The incidence of acquiring Swimmer’s Itch is unpredictable, but there may be factors that increase the likeliness of getting it. Dr. Raffel was part of a research team that investigated how wind conditions influenced the incidence of acquiring Swimmer’s Itch at a private Crystal Lake beach in northwestern Michigan, the Congressional Summer Assembly (CSA) Beach.

Over the course of four summers, lifeguards at CSA beach recorded various data points, including the total number of swimmers and self-reported Swimmer’s Itch cases, water temperature, wind speed, as well as wind direction.

The researchers analyzed this data and found that swimming by CSA Beach in the morning or on days with direct onshore wind perpendicular to the shoreline indicated the greatest risk for acquiring Swimmer’s Itch. The light produced at sunrise may cause the increased presence of avian schistosome cercariae in the morning, and the wind may shift these cercariae towards the swimming areas near the beach. It is important to point out that is not the wind that is directly increasing the risk of acquiring Swimmer’s Itch, but rather how the wind is moving the water carrying the avian schistosome cercariae that humans could be exposed to.

While these results may not be applicable to other lakes or locations within Crystal Lake due to their own unique biological natures, it is significant that the data collected at CSA was consistent over a long duration of time. Further research on the subject is needed.

To reduce the risk of acquiring Swimmer’s Itch, the Mayo Clinic recommends avoiding swimming spots that are marshy or where Swimmer’s Itch is common, not feeding ducks near swimming spots, and rinsing exposed skin to clean water after swimming.