The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line

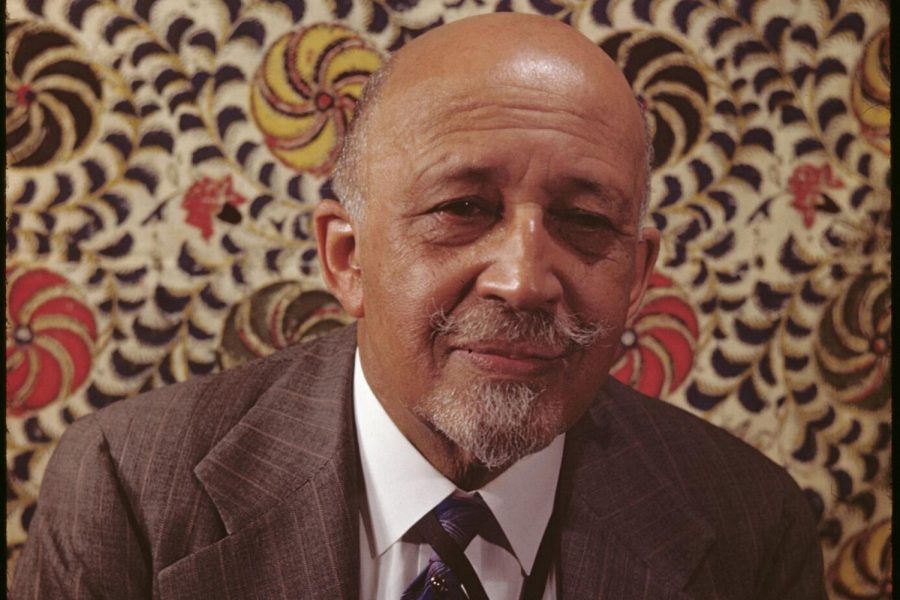

Photo Courtesy of Poetry Foundation

W.E.B. Du Bois’ pursuit of racial progress in post-Reconstruction era America was marked by many of the same obstacles that civil rights activists are confronting today.

“The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

These words, written in 1903, from the opening paragraph of W.E.B. Du Bois’ “The Souls of Black Folk” constituted his thesis that the Civil War was not the transformative moment in U.S. race relations that Abraham Lincoln had hoped for. Du Bois’ pursuit of racial progress in post-Reconstruction era America was marked by many of the same obstacles that civil rights activists are confronting today.

Among other horrid distinctions, 2020 will carry historical notoriety as being yet another year in U.S. history defined by issues of race.

COVID-19 proved itself uniquely capable of pulling back the curtain of American exceptionalism, effectively dragging all lingering skeletons of our nation’s foundational sin of white supremacy out of our closet for the world to see.

The pandemic disproportionately impacted African Americans, with the community seeing higher infection, mortality and unemployment rates than other demographics.

As if this weren’t bad enough, the injustices of police brutality once again rose to the forefront of public consciousness following the lynching of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis.

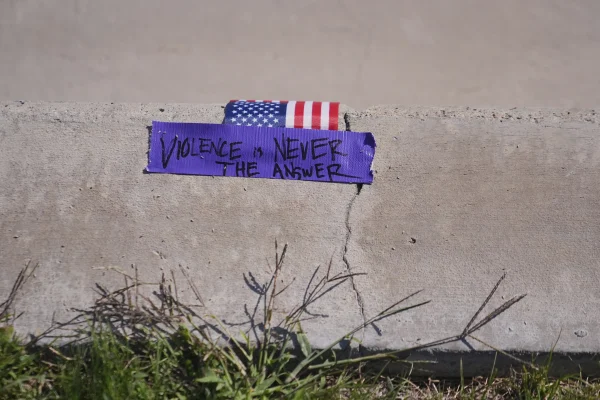

Following an explosion of protests across the globe in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, African Americans faced a new wave of racial resentment stoked by public officials and media figures. This backlash turned violent, leading to a spike in hate crimes.

This renewed racial tension culminated in the aftermath of the presidential election, when Republican officials made efforts to block certification of votes from Wayne County, MI. Specifically citing irregularities in Detroit, a city consisting of 78.6% African Americans, as justification for their actions.

As these racial injustices continue, the work of Du Bois seems a critically important piece in the intricate puzzle of race relations in America.

In our current racial climate, the ideas expressed in his collection of essays “The Souls of Black Folk” have become an invaluable historical resource for contextualizing the struggles of African Americans and how real racial progress can be achieved.

Du Bois’ words from 117 years ago, “The Nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land,” now seem almost hauntingly prophetic as the U.S. continues to face the consequences of failing to live up to its founding ideals of providing all citizens with a right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

“The Veil”, his metaphor for describing the separate racially divided worlds existing in America, seems more relevant than ever given the underlying social and economic conditions that have allowed the pandemic to ravage the African American community.

His theory of a black “double-consciousness”, defined by him as “this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt”, seems like a spot on description of the inherent double standards that make it hard for African Americans to excel in today’s society.

His criticism of Booker T. Washington established a crucial foundation of intellectual variety in the African American community. His outspoken disapproval of Washington’s approach to achieving racial progress helped establish the precedent that black intellectuals were not a monolith of beliefs.

This precedent is especially important for the modern BLM movement, as the push for racial equality faces an onslaught of moderate opposition.

Recently, opposition even came from former President Barack Obama. Using his voice as the most prominent African American in the world, Obama sat down for an interview last month and criticized the “defund the police” slogan as being too divisive.

Acting as a modern day Washington, Obama used the interview as an opportunity to peddle his usual tranquilizing drug of gradualism to the masses. Fueled by the urgency of now, BLM supporters fired back at Obama by pointing out the human lives being lost to police violence.

Du Bois himself exemplified this kind of urgency by using his work to portray the magnitude of the issue of race in America. His advocacy for black suffrage, equal education and economic opportunity were all tied to his fundamental belief that — if allowed to cultivate their traits and talents, African Americans would meet and contribute to larger American ideals.

To Du Bois, issues of race concerned all Americans. “The burden belongs to the nation, and the hands of none of us are clean if we bend not our energies to righting these great wrongs.”

Until we all embrace our burden in reconciling race relations in America, the U.S. will continue being defined by the problem of the color-line.

E.L.Smallwood • Jun 18, 2024 at 10:36 AM

June 18, 2024

In order to solve tough problems, there always needs to be ongoing stimulating dialog. Human relations issues like race is one of those tough problems and challenges that we face every day. These are among the complex issue of humanity that cover the complete spectrum of human existence

Dubois, and many others, have rightly recognized this. One of the tragic things about these times is that small, minded people, who often who consider themselves intelligent, try to shut down meaningful dialog. Creativity in thought is needed now more than ever.

How we chose to communicate, interact, and dialog is the real challenge. The highest moral mandate is to communicate in love. It is here that we are truly mission the mark.

Pastor W. Eric Croomes • Sep 20, 2023 at 11:28 PM

If nothing else, Mr. Obama is redux of Washingtonian perspective. Perspective, though, is not necessarily opposition. We need healthy and helpful debate as we navigate the meaning of being black in America.

Nibir K. Ghosh • May 26, 2023 at 12:58 AM

A very perceptive write-up on the contemporary relevance of Dubois’ The Souls of Black Folk that helps connect views of Dubois in 1903 with current racial scene in America.