Room 115 in the basement of O’Dowd Hall seems to be the only room not remodeled in the building. With six concrete pillars inside the classroom, old wooden stools and 90s cabinets, it was the perfect location for Professor Spencer-Wood to take the Anthropology Club back in time to the 1400s.

The Artifact Lab Night seamlessly began with a normal conversation in a stuffy storage room full of bones, artifacts and pottery.

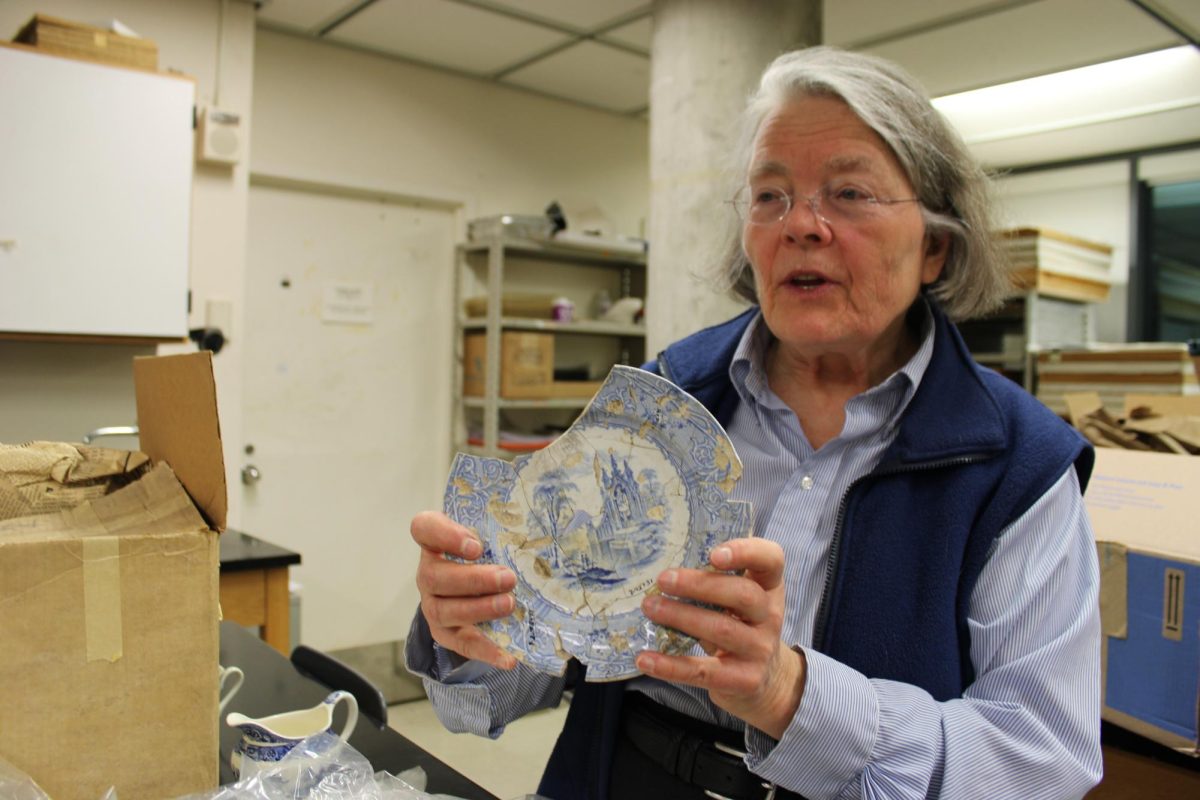

“This is part of a pitcher that I largely reconstructed, and part of other pitchers that are called Flow Mulberry,” Spencer-Wood, anthropology professor, explained while taking a dilapidated container out of a box. “I put this together, piece by piece. It was good for my headaches, very soothing. I like puzzles, it turns out.”

Just like that, the students were transported to the 1400s when Chinese porcelain was imitated in Europe.

“If you look at the design, you see it’s very Chinese, you see, it looks like a Chinese pagoda,” Spencer-Wood said. “That was the idea, to imitate Chinese export porcelain starting when the China trade was first started, Portugal went to China in the 1460s.”

In the same way a magician pulls a rabbit from a hat, Spencer-Wood pulled out relics from damp boxes and plastic wrap, opening up a conversation about their meaning, craft and historical relevance. Almost recreating an excavation, the anthropology professor would reveal the artifact and then explore its origins.

“I lived in Italy for a year, that’s how I fell in love with archeology, really, when I was 13, 14,” she said. “We went to all of the sites, we went to Pompeii, Herculaneum, all of the ancient sites. I fell in love with ruins, actually, while I was there. I like getting lost in the ruins, losing my family, particularly — not permanently, but you know.”

Labels, stamps and engraved details were all explored in depth by the anthropology professor. While she painted a picture of the excavation site with her hands, she dissected the theological relevance of what someone would discard as junk.

“This has got eight sides, that’s what’s called Gothic and the reason it’s called Gothic is that it is modeled after baptismal fonts in churches,” Spencer-Wood said, returning to the Chinese imitation whiteware. “It symbolizes the sacredness of women, and particularly mothers in the home. It became, from the 1850s and later, very popular.”

In a span of five minutes, the anthropology professor would examine the blue engravings of the pitcher to point out the Chinese style, and all of a sudden, the conversation would turn to Puritan consumer choice. The time machine of her expertise was swift and smooth, continuously dropping the jaws of students.

“The different meanings I’m finding out about really fascinate me about this,” she said. “Because when I started, I was just doing trade networks, and that’s, you know, interesting, especially when you’re talking about this little town, hill town.”

Most of the relics she dissected with the Anthropology Club were part of her six-year-long PhD dissertation project. She excavated 20,000 pieces and reconstructed the artifacts from the Knight family general store in Dummerston, Vermont, an experience she carries with pride and remembers with laughter. The store was taken down piece by piece and put back together at the Old Sturbridge Village in New England.

“We have in archeology, what’s called the tongue test,” Spencer-Wood said. “If you are in the field, we do this — yeah, gross — and you recover one [earthenware artifact], if you put your tongue to one of these, you can feel the water getting pulled out of your tongue into the ceramic.”

In a little over two hours, the Anthropology Club went from Portugal to New England and back, tracing the trading routes, meaning and cultural relevance of glass bottles, clay jugs and porcelain cups. Meanwhile, Spencer-Wood revived her anecdotes on the field and cultural observations with a casual expertise.

“One of the things archeologists learned to do is look closely, which goes right along with being a feminist, who reads closely, which is also what I do,” Spencer-Wood said.