On Oct. 15, Oakland University explored the possibilities of integrating artificial intelligence into the academic sphere with a day-long exposition of guest speakers, university projects, discussion and education on AI.

“What we’re dealing with in 2024 is an evolution of artificial intelligence, not least the emergence of large language models with the capability of incredible processing tasks,” Dean of the Honors College, Graeme Harper, said. “[AI] has an incredible power to do processing that we’ve not seen before in every single part of our lives and in every single industry and throughout education of course.”

OU AI Day began with, higher education consultant and AI researcher, Dr. Derek Bruff’s presentation on teaching and learning in the age of generative AI.

“Large language model-based tools speak but don’t think they put words together in clever ways, in sensible ways, but they don’t actually know things,” Bruff said. “I like to think of them as wordsmiths, not oracles.”

Bruff’s first argument regarding AI was that teaching with and about artificial intelligence is an equity issue.

“The students that are the kind of minoritized students that we have in our classes are less likely to have access to these tools and less likely to have know-how around these tools,” Bruff said. “If jobs are increasingly looking for the skill set, then I think it’s on us to help provide that thoughtful skill set for all our students.”

Bruff compared the free version of ChatGPT to the paid version as well as the prompts imputed by an AI literate individual and an AI illiterate individual to reflect upon the equity problems around AI.

Changing learning goals, evaluation methods, exam tools, grading rubrics and career focuses have become central discussion in universities across the world, Bruff explained.

“We switched from assessing the final product, such as an essay, to evaluating the writing process itself,” Bruff said. “We’ve decided that it isn’t important whether or not our students are using AI to write their papers. In fact, we encourage them to use AI so we don’t write our rubrics about whether the student has good grammar or whether the work is organized.”

In Computer Science, a shift in focus from code generation to code evaluation would be a proactive use of AI, Bruff said. Similarly, in creative fields, AI would eliminate the ‘struggle’ of the creative process, something beneficial for mass marketing but not for creative development.

“‘Why would I pay all this tuition to learn to write and then have a chatbot do it for me?’ That was a student paying her way through a prestigious journalism school. Someone else then put their hand up and said, ‘The students in my composition course see the course as an obstacle, not an opportunity,’” Bruff said, recalling a past conference. “I want to acknowledge that teaching the struggle is going to be easier in some cases and in other cases.”

This was only the introduction to the developing idiosyncrasy of humans interacting with exponentially rapid AI developments. Breakout sessions took place after the presentation to discuss how disclosing the use of AI would look in a classroom, how to restrict and integrate it into the course curriculum and how to avoid misinformation as AI advances.

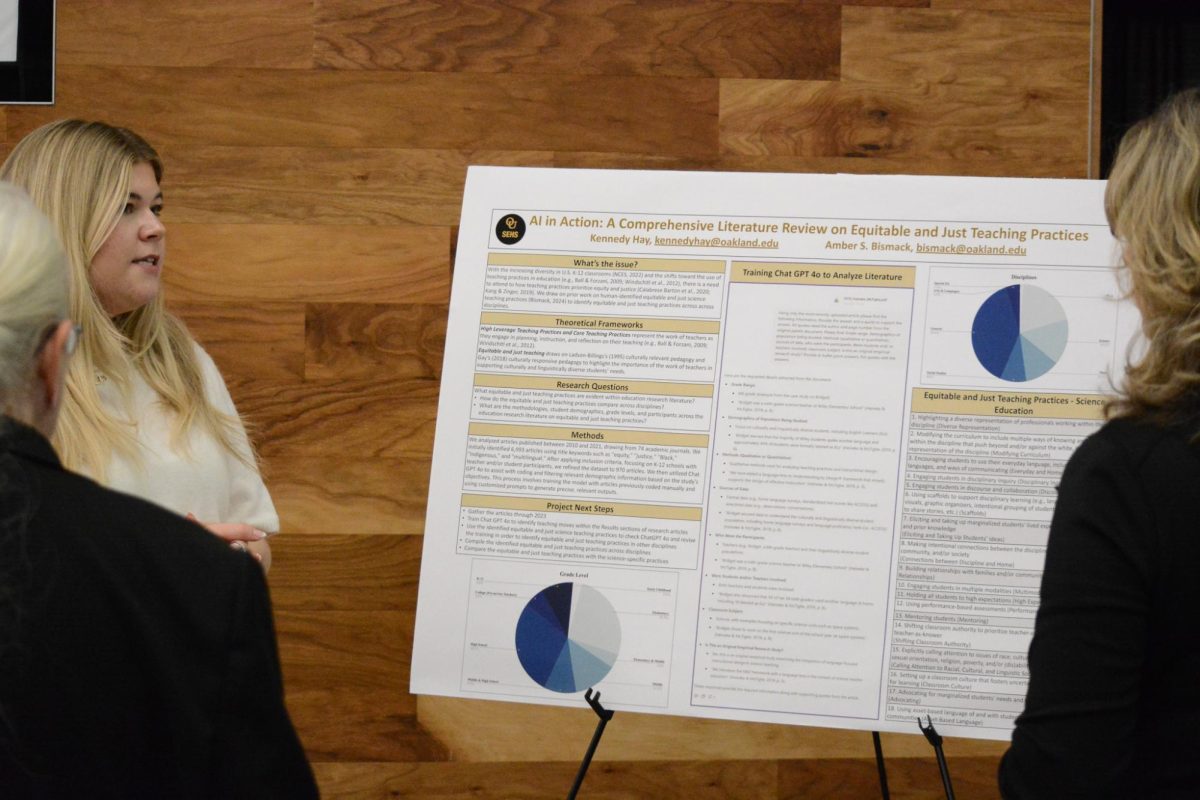

Students and faculty exploring the use of AI in education had poster presentations by noon, followed by a final panel discussion on the strategies to further advance the integration of artificial intelligence into higher education.

“Understanding the concepts of photography is going to help you learn the buttons on your camera and what they do, but I would argue that it also works the other way,” Bruff said. “As you’re playing around with different settings and taking photos in different situations, you’re starting to get a better sense of those conceptual skills associated with photography, and that’s where I’m really excited about the use of AI.”