Alumnus wins Pulitzer Prize with The Washington Post

Photo Courtesy of Salwan Georges.

At 12 years old, Salwan Georges and his family immigrated to the United States from Syria, after having fled Iraq in the 90s. Georges didn’t speak English and had to adapt to a new way of life.

Sixteen years later, Georges was honored with the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Journalism for his work with The Washington Post photo staff’s “2°C: Beyond the Limit” series.

The Pulitzer winning series was published on Sept. 11, 2019. It showcased the lasting effects of rising global temperatures around the world, with Georges focused on the Qatar and Japan entries into the series.

In 2019, Georges and The Washington Post staff were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Journalism but did not win the award. In 2020, they also were a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for their work on the opioid crisis.

“I really didn’t expect to win this year as a group, but we worked really hard on that story,” Georges said. “Awards are never my concern. I am more focused on helping people and shedding light on these issues. I know there are a lot of photojournalists who work all year just to win awards, but that isn’t why I got into photojournalism in the first place.”

For Georges, the awards were never the reason for becoming a photojournalist, but he was excited for “2°C: Beyond the Limit” to get more recognition.

“It makes me happy when things like this happen because it is going to shed light on this issue,” Georges said. “Not only will it make people curious about it, it will make people go back, read and spend some time seeing why this work was awarded.”

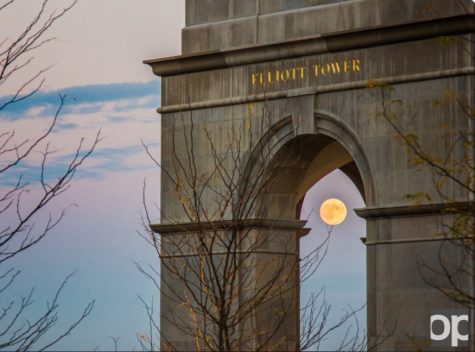

The 28-year-old photojournalist spent two years at Oakland University studying photojournalism after studying at Oakland Community College. While at OU, he worked at the campus newspaper, The Oakland Post, as the photo editor.

While working for The Oakland Post, Georges spent only a few months as a photographer before being promoted to photo editor. At OU, he learned to become a better journalist — not just a photographer — which helped his photos tell stories.

While he was working at The Oakland Post, he indulged in a passion project, working to document the Iraqi American community around Dearborn. The story was picked up by The Washington Post in 2017. This project came as a “wake up call” after a death in the family.

“It came calling when one of my family members was killed by ISIS,” Georges said. “I realized I need to become more of a storyteller and tell the story of people in suffering.”

Georges drew from his experiences as an immigrant — when he had to assimilate to a new culture with little knowledge of the English language.

“It’s the struggle you face as soon as you get here,” Georges said. “I was thrown in a high school without a tutor, and we didn’t get the proper education. Imagine not knowing the language and getting thrown into high school as a freshman. I faced a lot of difficulty with the language and resettling into the culture.”

He believed his experience was similar to that of many immigrants who come to the United States. His work around Dearborn was meant to showcase the struggle he and his family endured.

“It made me continue the story of my family and many others where I worked a lot in Michigan on stories about immigrants — especially in Dearborn,” Georges said. “I think being an immigrant helped me see things differently and tell stories in a very personal way.”

That project helped launch his career as a photojournalist. Georges interned with the Detroit Free Press while freelancing for other publications, then was hired as a full-time photographer. After working there, he moved to The Washington Post, where he works as a staff photographer.

Adina Schneeweis has taught at OU for 11 years and has taught photojournalism since the winter semester in 2010. She had Georges in class, and since then has been “obnoxiously” sharing his work with her classes.

Schneeweis remembered a time while Georges was in her class, where he told a restaurant to act as if he wasn’t there while doing an assignment. After taking photos, Georges was surprised at the lack of hospitality he received, but then Schneeweis reminded him of the way he set the photoshoot up.

“He was expecting them to show a level of hospitality or politeness,” she said. “He said he walked in and asked them to pretend like he wasn’t there, and I said ‘well, they were pretending like you weren’t there.’”

Georges went back to the business, adjusted his approach and got the personal connection he was looking for.

“It was really sweet,” Schneeweis said. “He went back and he said ‘this time I put my camera down and just made myself more available to connect with them,’ and the photos were so much warmer and considerably stronger once he decided he didn’t want to just be a fly on the wall — that he wanted to have a relationship with his subjects.”

Schneeweis never felt like she had to teach Georges much, due to his “innate talent” and previous experience. She felt like Georges captured photos easily.

“He has a powerful way of listening and he has a very piercing gaze,” Schneeweis said. “When somebody who is looking at you that way is also listening to you very intently, you really feel like opening up. He wants to know who you are and wants to know your story. People trust he won’t abuse a mood or a feeling, and they’re comfortable around him.”

During his time as photo editor at The Oakland Post, Georges raised the “standard of excellence” for the photography team, according to Holly Gilbert, the adviser at the time.

“What was so impressive was not just his talent, but how he mentored the other students and would teach them about photography,” she said. “I’ve been advising the Post in some form — either directly or indirectly — for 26 years and that was a time of the most professional, moving, quality photo coverage that we’ve ever had.”

Georges was in Garry Gilbert’s introduction to journalism class, where Garry discovered his talent, and immediately recommended he join the campus newspaper.

“You could choose to shoot the same thing as him, and then be like ‘what’s the matter? Why does my image not live and breathe like his does?’” Holly said. “Most of us take pictures of people and it shows how they look, but he takes pictures that show their soul. You can just see into their soul — the way he captures them.”

Oona Goodin-Smith was the editor-in-chief while Georges was the photo editor at The Oakland Post. Goodin-Smith now works at the Philadelphia Inquirer as a breaking news reporter, about 100 miles down I-95 from the Washington Post.

During the 2014-15 school year, Goodin-Smith and Georges worked closely to produce weekly issues. Goodin-Smith remembered the quality work Georges produced, as well as the knowledge he shared with the staff about photography.

“He has an outstanding visual eye and sense of storytelling, he also has a sense of generosity and takes time to teach others his skills — it doesn’t seem like a burden, he seems to enjoy it,” Goodin-Smith said. “He was very generous in taking time to teach others on staff. I think that just made everybody better.”

Georges shared his knowledge with Goodin-Smith about photos and photo editing, which she has since used in her professional career.

“He took time to explain squaring up a shot or what made a photo interesting,” she said. “He would look at the cover very meticulously, and we made sure all of the crops of the photos were perfect. As a journalist now, you have to take video and photo a lot on your own and I do think about things that I remember learning from him.”

Georges believes that his time at OU helped him add more of a storytelling aspect to his photos, something he felt wasn’t as strong before his time at The Oakland Post and Oakland University.

“The Post and Oakland University helped me shape my journalistic skills, which is very, very important as a photographer,” he said. “It helped me become more of a photojournalist — I’m very thankful I got that experience. I can say I’m a journalist as well as a photographer.”

The most important aspect of Georges’ photojournalism is building relationships with the subjects. This aspect of human interaction is what Georges believes is the most important in photojournalism and has carried with him since the start of his career.

“You can’t just have the approach of being a photographer and not caring about the people you are spending time with,” he said. “Getting that education that helps you become more of a journalist is very important in my career.”

The Washington Post team and Georges are working on COVID-19 coverage — specifically around Capitol Hill currently — during the lockdown periods. Georges has continued to cover the 2020 presidential election, initially covering Sen. Bernie Sanders in January before Sanders dropped out of the race.

The 2020 election and COVID-19 coverage is what Georges expected to dominate the majority of the year, but with journalism, he has learned to never rule out the unexpected.

“Who knows, in a few months I could be in a different country,” he said.

Despite winning a coveted award for journalism, the most important thing for Georges when sharing a story is the response — never the awards.

“I feel like I’m most successful in telling a story when there’s an action or movement — not by the awards,” he said.