The watchdog of truth

Room 376 in South Foundation Hall is a copy of all the other classrooms in that building. Stark, white walls meet a tan floor where gray tables and slightly darker chairs sit in symmetrical rows facing the dusty chalkboard in front.

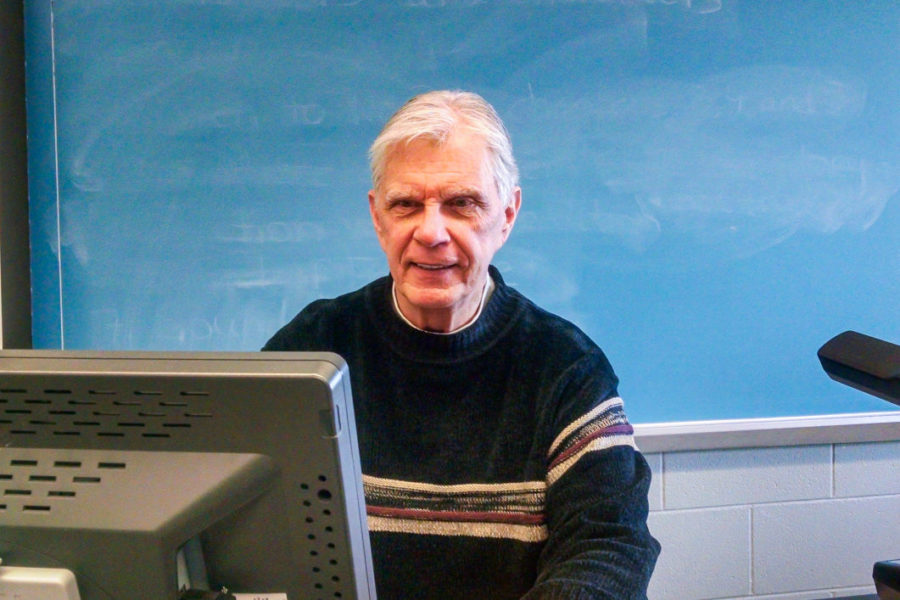

A dull landscape, indeed. That is, until broadcasting professor Gene Fogel walks into the room.

A towering man, Fogel lumbers over to the table, dressed in all black except for the gold bracelet on his wrist and the WJR ring on his right hand.

Fogel always wears that ring – a token of the 43 years he has spent as an investigative reporter at the Detroit news/talk station, WJR 760 AM.

In those four decades, Fogel has won numerous awards including a spot in the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame. One of his investigations led to the release of an innocent man from prison. Another one led to indictments and resignations at Detroit’s U.S. Bankruptcy Court.

The key to Fogel’s success is not simply his light-hearted humor (he constantly jokes to students that he switched from television broadcasting because he has the face for radio), but his deep-seated loyalty to being a journalistic watchdog, to being thorough in his reporting and, above all else, to being ethical.

Despite years of reporting in Detroit, a tough market at times, Fogel always manages to add humor to his otherwise serious lessons.

As we begin our interview, he refers to a current ethics lesson, mentioning the recent events surrounding NBC’s Brian Williams. Williams was a renowned journalist, pulling in around 10 million viewers a night to “NBC Nightly News” – that is, until a few weeks ago.

In early February, his ethics were deeply questioned when it came to light that one of his long-told Iraq war stories, which involved his being in a helicopter that was shot down by an R.P.G., was an outright lie.

Fogel, obviously disturbed and confused as to how someone could do this, explains that instances like these are what give journalists a bad reputation.

“I know in our everyday lives, we lie, we exaggerate…no honey, you don’t look fat in that dress,” he said, serious, but with that hint of Fogel humor. “But, you’re a journalist reporting a story. You can’t distort the facts to make yourself look better.”

For Fogel, this rule is law.

He said the most common ethical dilemmas he faced in his career involved: when to use stories with anonymous sources, how to handle stories involving people of public trust, staying objective despite personal beliefs and respecting the privacy of those dealing with great pain.

Fogel said he hates what he calls “ambush journalism,” where reporters stick their microphones in people’s faces and yell questions at them.

Instead, Fogel introduces himself and asks if he may speak with sources. If they say no, he explains he will be talking with others so it could be in their best interest to speak with him.

If they refuse again, he leaves them alone and either writes that they refused to comment or finds another source for the information.

“I’ve seen reporters who continually hound people, and that’s not my style,” Fogel said. “I want people to feel comfortable with me. I want them to respect me.”

Fogel has missed out on stories where sources cracked under the constant pressure and admitted to a crime or provided new information.

“I’ve missed that story, but I haven’t challenged my ethics. I can still look at myself in the mirror,” he said.

Fogel’s journalistic ethics are really just an extension of his personal morals. They are not something he must practice or “turn on.” They are simply there – natural.

Despite today’s fast-paced media society, Fogel relies on those deep-seated traditional journalistic values that he honed over 40 years ago, the most important being accuracy.

As Fogel puts it, “I would rather be second and right than first and wrong.”

In a time when the public is questioning journalists’ ethics and value as watchdogs of democracy, it is professionals like Gene Fogel that lay the groundwork for future reporters to walk upon – objective, fair and accurate.