The bodies in the basement

In the basement of one of Oakland University’s oldest buildings, at the end of a long, dimly lit hallway, is a room kept at 68 degrees year-round. The chill is necessary to slow the decomposition of the human bodies inside.

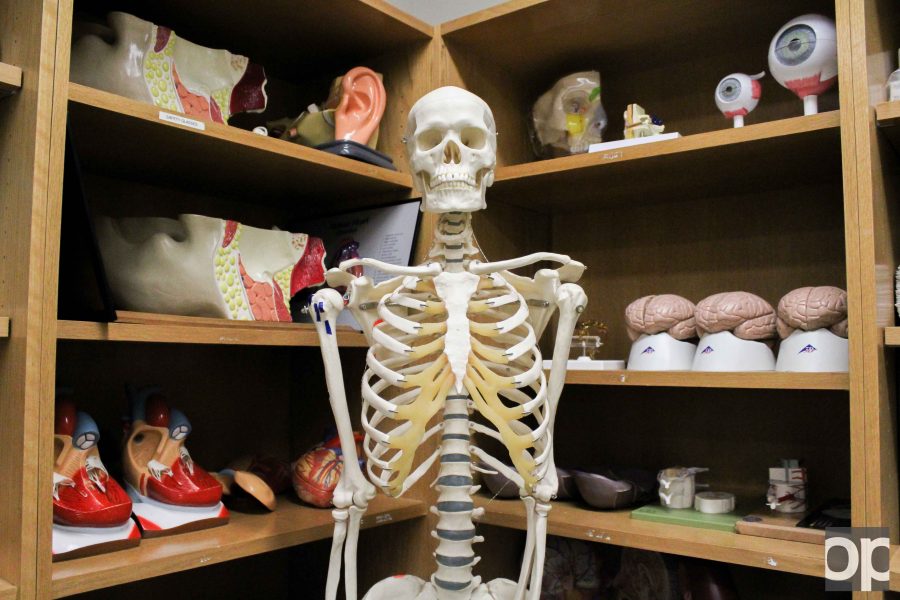

Many students fulfilling their general education requirements upstairs are unaware that Dodge Hall of Engineering is home to BIO 206: Human Anatomy Laboratory.

In the semester-long lab, students use human cadavers to build their understanding of the musculoskeletal and major organ systems, according to OU’s course catalog.

“By the end of the semester, the cadavers became quite odorous,” said senior health sciences major Jessie Felix, who took BIO 206 in fall 2014.

Where do the students come from?

Most of the students who enroll in BIO 206 are studying pre-med, biology, nursing, health sciences, exercise science or other health care-related fields.

“We had a modest biology program 10 or 12 years ago, and then everything bombed up,” said Arik Dvir, chair of the Department of Biological Sciences. “There was a huge jump in interest and enrollment.”

In the program’s beginning, there were two sections of the anatomy lab offered per year. Now, about 18 sections of BIO 206 run each fall and winter. Each section is capped at 36 students and uses two to four cadavers.

“We are offering as much as we can,” Dvir said. “We cannot offer more. We’d have to have another building to offer more.”

According to Dvir, the university doesn’t receive much income from running BIO 206 because it is a one-credit course. But having an undergraduate anatomy lab sets OU apart from other schools.

“We have people that come from other institutions just to take the labs,” he said.

Where do the cadavers come from?

Cadavers used in university labs are acquired through willed body programs, through which donors or their families declare that they would like to donate their bodies for research or teaching.

“Each medical school has its own charter, and they have a contract that they have persons who want to donate their bodies sign,” explained Mary Craig, who has over 30 years of experience in the field and has taught BIO 206 at OU for the past five years.

Donors can specify the length of time that their bodies may be used. For example, they can sign one- or two-year contracts, or they can allow their bodies to be kept as long as they are useful.

The cadavers used by OU’s biology department are obtained from loan programs with other universities, including University of Michigan and Wright State University.

OU has also borrowed from the University of Toledo in the past, though Craig prefers sticking to Michigan institutions because legislation can vary from state to state.

But in order to participate in these loans, there are some hoops to jump through. Courses have to be approved by the willed body programs, among other requirements.

“We had to hit all their tick boxes for us to be able to accept their cadavers,” Craig said. “And so, part of it is the respect issue and having a code of conduct already in place, having an appropriate setting, having an appropriate room with appropriate housing — which would be a ‘cold room’ or care facilities wrapped up with that. And then we also have to have a teaching program.”

In total, about 14 cadavers come through the program each year.

Working with the cadavers

They arrive in bags, embalmed and ready for dissection.

Donors are tested for bloodborne pathogens and communicable diseases before they are accepted to a willed body program, and the cadavers are tested again prior to embalming.

They are treated with a combination of chemicals, including glycerin (a vegetable oil product), ethanol, a fungicide or bactericide, and Dis-Spray — an embalming spray that preserves tissues, deodorizes and prevents mold.

Craig described the cadavers as feeling “like a dense rubber.”

“It doesn’t feel like a human anymore,” Dvir said. “ . . . It feels like more like a material almost . . . It doesn’t have that human feeling.”

Once they’re at OU, the cadavers are transferred onto cadaver trays or downdraft tables, which are made of stainless steel and enclose the cadavers when they are not in use. The identities of the donors are protected, and each downdraft table is labeled with the cadaver’s identification number and gender.

The downdraft tables connect to the laboratory’s extensive ventilation system, which keeps students from inhaling any hazardous materials and prevents the room from smelling.

“You’ll find our cadaver lab doesn’t smell,” Craig said. “Some other cadaver labs that don’t have the same system that we have can smell funny. They smell kind of, like, sweet.”

Dvir contended that the lab does smell, at least a little bit.

“I’ve been doing anatomy for over 30 years, so I probably have killed some nerves there,” Craig joked.

Instructors and TAs must regularly bathe the cadavers in Dis-Spray to keep them damp. Dehydration makes them less useful and opens the door for mold.

“They get dried out quickly, so we do the best we can,” Craig said.

When class is not in session, the tables are wheeled into the “cold room,” which is climate-controlled to preserve the cadavers.

Working with the students

In Craig’s BIO 206 course, students begin the semester by studying bones for three weeks before moving into the “wet lab,” the part of the course that works with cadavers. Other professors introduce their students to the cadavers earlier on.

The first day of class, Craig explains to her students that the course is cadaver-based (and is puzzled to sometimes learn that a student or two wasn’t aware of this when enrolling). She tells them how OU obtains the cadavers.

“We talk about the ethics, that you have to remember that this is someone’s grandma, someone’s mother, someone’s brother, someone’s sister, and so they at all times have to be treated with respect,” Craig said. “It’s a gift that you get to use them for these purposes.”

Students are also asked to sign a code of conduct on the first day.

According to Craig and Dvir, students’ instinct to use cell phones during class presents a challenge to anatomy labs, where respect is of utmost importance and photography is prohibited.

“We were given very serious instruction on how to act,” Felix said. “Cell phones were not even allowed to be seen out of pockets, and I don’t think anyone even giggled because we all had a large amount of respect for the bodies in front of us . . . It just wasn’t something to mess with.”

Students do not dissect the cadavers themselves. Instead, they learn through prosection — TAs perform the dissections in advance to prepare for each lesson.

But that’s not to say that the lab isn’t hands-on.

“My favorite part was definitely holding the human brain in my hands,” Felix said. “ . . . I had this thought like, ‘This is what made this person who they were, every thought, every movement, every emotion went through here for so many years.’ It was a truly awe-inspiring moment for me and gave me a ton of respect for the cadaver in front of me.”

At the end of the course, the cadavers are returned to their families, and the students walk away better prepared for their careers.

Both Craig and Dvir emphasized that any student can enroll in BIO 206 as an elective, even if their majors aren’t related to medicine. An anatomy concentration or minor is also in the works, and interested students can join the Anatomical Society of OU, a student organization focused on the human body.

“There are potential links to anthropology, archaeology, bio engineering and art,” Dvir said.

An occasional art student takes the lab to learn about replicating the human body in his or her work.

“They shouldn’t be afraid of the science,” Craig said.