Winter College’s department made $55 million in last decade

After much controversy over February 2016’s closed board meeting and Winter College conference in Bonita Springs, Florida, The Oakland Post takes an in-depth look at the money involved.

After the campus community learned about the Board of Trustees retreat and sixth-annual Winter College donor event in Florida in February 2016, some students and faculty at Oakland University became angered.

However, the Department of Development and Alumni Relations (DDAR), which organized Winter College, brings in more money than it spends: $55,381,907 in profit over the last decade.

The DDAR has hosted six annual Winter College events in Florida. At these events, significant donors and alumni are invited to attend talks and meet one-on-one with Oakland staff, administrators, deans and faculty.

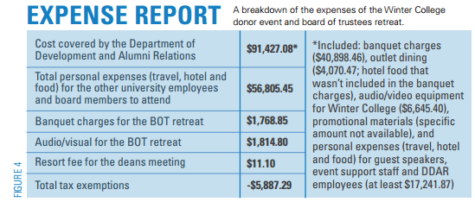

Oakland paid the travel expenses for 42 employees and board members.

“The staff/administrator count has been proportional to the guest counts overall in past years,” wrote John Young, vice president of communications and marketing, in an email. “2016 had a higher number of staff/administrators attend due to events surrounding Winter College.”

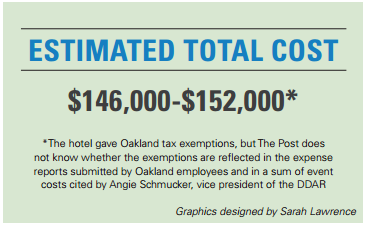

The board meeting and February 2016 Winter College cost the university between $146,000 and $152,000, depending on whether tax exemptions were taken out of the hotel bills before employees turned in their expense reports. This is according to event costs cited by Angie Schmucker — vice president of the DDAR — and to nearly 800 pages of documents acquired through the Freedom of Information Act that included the expenses of Oakland employees, trustees and the master hotel bill. The Post got the documents from the Oakland University Office of Legal Affairs, General Counsel and Secretary to the Board of Trustees.

The total expenses of $146,000 to $152,000 are .0575 percent to .0598 percent of the university’s total fiscal year 2016 (FY2016) general fund adjusted base budget of $253,754,100. FY2016 runs from July 1, 2015, through June 30, 2016.

The total expenses of $146,000 to $152,000 are .0575 percent to .0598 percent of the university’s total fiscal year 2016 (FY2016) general fund adjusted base budget of $253,754,100. FY2016 runs from July 1, 2015, through June 30, 2016.

The general fund is mostly made up of tuition and state appropriation (81 percent tuition, 18 percent appropriation for FY2016).

Donations do not go into the general fund, Schmucker said. Instead, they go into any of the some 800 gift funds throughout the university which direct gifts to where they can be used. The money can be earmarked by the donor for specific departments and can even be designated for specific projects.

The DDAR did not pay for the trip in full. Instead, according to the documents and Schmucker’s event costs number, it spent $91,427.08. The money covered event costs and the travel expenses of four faculty speakers – David Dulio, professor and chair of the Political Science Department; Judith Fouladbakhsh, associate professor of nursing; Tamara Hew-Butler, associate professor of exercise science; and Peter Trumbore, associate professor of political science. The rest paid for golf with donors and the travel expenses of DDAR employees.

Profit

The DDAR’s $91,427.08 expenditure was 1.58 percent of its total FY2016 budget of $5,776,873.

The department’s total budget seems enormous until it’s compared with how much money the department brings back in donations. As of May 18, Schmucker estimated that FY2016 would bring in just under $10 million in new donation commitments, almost double the budget. Official documentation of exact commitments for FY2016 was not posted online as of Sept. 13.

This is a trend that has been going for a decade. From FY2006 through FY2015, the DDAR has brought in more money in donation commitments than it spent. If you count Schmucker’s estimated $10 million in new commitments for FY2016, then the DDAR has brought in $59,605,034 more than its budgets since the beginning of FY2006. If you don’t count Schmucker’s estimate, that sum becomes $55,381,907.

These donation commitments may take multiple years to pay out in full, as the sums may be endowed — i.e. invested so Oakland may use the resulting interest — or paid in installments. But taking a long-range view, the DDAR has made a profit on its budgets in the last decade.

The DDAR’s average budget was $3,835,425 per year from FY2006 to FY2015. During the same time period, the department brought in an average of $9,373,616 in total donation commitments per year, netting an average profit of $5,538,191. It was during this decade that the first five annual Winter Colleges were held.

The largest amount of total donation commitments Oakland received in the last decade was $19,777,124 in FY2009, when the DDAR’s budget was $3,349,297. It received the lowest amount in the decade – $4,757,045 – in FY2006, when the DDAR operated on a budget of $2,873,392.

How donations at Oakland work

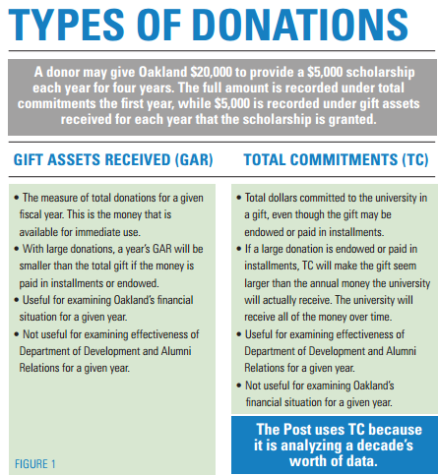

Gifts to the university are measured in two ways. The first is in gift assets received, or how much cash and other assets Oakland receives in a fiscal year. The other way is total commitments, or pledges of funds that are promised to the university by donors. The pledges may take more than one year to be donated in full (as they may be endowed or paid in installments), but the entire sum is listed once on the university financial reporting.

This article examines total commitments instead of gift assets received because those records were more readily available. They also reflect a more immediate view of the work the recent DDAR administration has done. If this article were to examine gift assets received, the picture would not be complete, as it would credit the recent DDAR administration for previous endowments and large installment donations, and it would ignore the money the recent administration has lined up.

Total commitments vary greatly by year because some donors will bestow large amounts of money to Oakland upon their deaths. Years in which total commitments jumped may indicate that a donor passed away, Schmucker said.

The amounts also fluctuate because Oakland is a relatively young university, having been founded in 1957. Its donor base is not nearly as large as that of the University of Michigan, for example, which was founded in 1817.

Donations are increasingly necessary for Oakland. Base state appropriation has gone from funding 71 percent of the university’s general fund in FY1972, to 44 percent in FY2002, to 18 percent in FY2015, according to numbers from the meeting of Oakland’s Board of Trustees on July 7, 2015. According to the Michigan House and Senate Fiscal Agencies, in FY2015 Oakland received the lowest per-student state appropriation of the 15 public universities in Michigan: $2,778 per student against an average of $5,114.

Press coverage

Even though the money checks out, 2016’s Winter College and Board of Trustees retreat racked up bad press from local papers.

The Detroit Free Press broke the story on Feb. 11 with an article about the Board of Trustees retreat, which it said took place Feb. 3-4. The article reported that seven administrators, three support staff, a consultant and six members of the board attended. The article did not mention Winter College, which occurred Feb. 4-6.

The Free Press quoted an emailed Oakland statement: “The retreat provided uninterrupted time for trustees to develop a better perspective on complex topics.” According to the article, Oakland President George Hynd discussed five and 10-year plans, “risk management and strategy on enrollment and student life.”

Later that evening, Nolan Finley of The Detroit News wrote an editorial criticizing the university. He accused the board and administrators of leaving the state to skate past the Michigan Open Meetings Act, which “[requires] certain meetings of certain public bodies to be open to the public,” according to legislature.mi.gov.

Finley also noted that Chief Operating Officer Scott Kunselman went on the trip. Kunselman is a controversial October 2015 hire and former board member paid $325,000 a year, in part so that Hynd has time to network with donors.

The Oakland Press chimed in on Feb. 12 and was the first publication to mention Winter College by name in addition to the board retreat. It added that Mark Schlussel, who attended the trip and was then-chair of the board, said the board retreat was not subject to the Michigan Open Meetings Act because it was not a formal meeting and no decisions were made.

On Feb. 15, The Oakland Post reported perspectives from the campus community. Nick Walter, then-Oakland University Student Congress (OUSC) president, said he was “gravely concerned” that the board held a closed meeting and that he expected the board to operate in a more open manner.

Madison Kubinski, then-OUSC vice president, said that OUSC did not support the meeting and would make efforts to increase transparency. Annie Meinberg and Liz Iwanski, then-student liaisons to the board, said they understood the purpose of Winter College, but like Finley, were concerned that Kunselman attended the trip.

Ken Mitton, president of the American Association of University Professors at Oakland, which serves as a faculty union, questioned the location of the events.

“We suggest that it would have been wise to hold this planning retreat in-state, even within Oakland County,” he said.

That same day, The Oakland Post’s then-Editor-in-Chief Kristen Davis published an editorial criticizing the board for holding an informal meeting that most students would not be able to go, and casting doubt over the practical nature of the word “informal.” She repeated her discontent in a farewell editorial on April 6.

On June 4, the Detroit Free Press reported that the university spent as much as $155,000 on the trip and that Hynd’s and Kunselman’s wives also attended on the university’s dime. Hynd told the Free Press that $2.7 million in “asks” were made of event guests but also acknowledged that the timing of the trip was bad – tuition for the 2015-2016 school year was raised 8.48 percent in July 2015, and Kunselman’s hiring had stirred up controversy in October.

Anders Engnell, current vice president of OUSC, created a petition against the trip on June 8, which had 1,442 signatures as of Aug. 27. Engnell and Zack Thomas, current OUSC president, presented the petition to Hynd on Aug. 15.

According to Oakland University Communications and Marketing, Hynd meets with student government leaders on a monthly basis to discuss ideas and concerns.

The press coverage of the trip was centered mostly on the closed board meeting (the ethics of which are beyond the scope of this article), but the cost of Winter College caught some flack as well.

Change of plans

Of the two events, Winter College seems more beneficial. It at least checks out financially.

It is also worthy to note that, although not all alumni donate, more Oakland alumni live in Florida than in any other state beside Michigan (2,024 lived in Florida, compared with 71,665 in Michigan, according to university numbers from November 2014). About 15 miles from Bonita Springs — where the 2016 Winter College was held — is Naples, Florida, where 115 alumni live.

Fifty-four percent of donors were Oakland alumni in calendar year 2015, Schmucker said. That value usually ranges between about 50-60 percent each year, though that percentage does not equate to the percentage of total dollars donated that are given by alumni as opposed to non-alumni.

Although the DDAR is firmly in the black, the university is rethinking Winter College.

“New leadership in the Office of Development and Alumni Relations undertook a review of engagement activities in preparation of an acceleration of major gift fundraising efforts at OU,” Hynd told Oakland University Communications and Marketing on June 13. “Based on this, our regional engagement in Florida, historically referred to as Winter College, will occur in a new format in 2017. This format will be more efficient in reaching more donors with fewer staff in more geographic areas. No retreats are expected to occur connected with these fundraising and engagement events.”

The new leadership is Schmucker. She did not officially start her job until March 1, 2016, after Winter College 2016 had been planned and executed.