Case closed, student moves in

What does it mean to be a student at Oakland University?

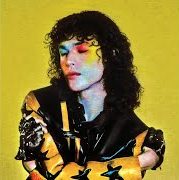

As it is becoming evident in the case of Micah Fialka-Feldman — OU’s own nationally-known poster boy for equality — it’s a lot more technical than one would imagine.

Fialka-Feldman recently won his long, drawn-out court battle against OU in his plea to live on campus (see cover story on page 6). He finally won that battle last month after a judge said that OU discriminated against him solely because of his disability.

OU did not make a fuss when Fialka-Feldman moved into Vandenberg Hall Monday, surrounded by his friends, his supporters and the media. However, OU is planning on appealing the court decision, saying that he was not discriminated against because of his disability.

The argument goes like this: Fialka-Feldman, despite his enrollment in an official OU program, is not a student because he is not seeking a degree and never went through the formal admissions process.

Does OU’s position hold water?

Of course he didn’t go through the normal admissions process. He was admitted into a program that was created partly because the normal admissions process is extremely difficult for those with cognitive disabilities to complete. The program, OPTIONS, caters to those students who want a higher education but cannot complete the requirements for a degree.

Fialka-Feldman is one of the first two students to be graduating from this program in May 2010. The program only serves eight students, and isn’t accepting any more.

It is a shame, because the program enables equal opportunity for learning without compromising the requirements for an OU degree.

Equal opportunity is the essence of equality. Anything greater than opportunity may shift the weight on the scales. It is a delicate balancing act and there is seldom a clear choice on how to ensure fairness. Perhaps the choice should be to consider compassion and reason and each circumstance:

Fialka-Feldman used to have to take two buses to campus, and that took him about two hours each way.

The university has a reasonable fear of opening up floodgates for more “non students” to live on campus, when housing is already overcrowded. The OPTIONS program is small in number. But the fundamental question seems to be, should those enrolled in this program be acknowledged as students?

Let’s consider: They pay for their program just the same as “normal students” pay for their tuition, they buy their books, they make sacrifices to be here, and they are involved on campus.

Arguably, Fialka-Feldman is more involved on campus than most students. The fear of setting a bad precedent is unfounded, if we consider the above.

Yes, there needs to be criteria for living in campus residencies. Dorms and student apartments shouldn’t be shared with TGIFriday’s employees who aren’t students, faculty members, or people who want an apartment close to the freeway. That would unreasonably take away from what student housing is.

But do we need to have a requirement that somebody must be seeking a degree when there are programs in place for people who cannot reasonably achieve that? Is that fair?

Does housing go through their records and ask for something back if a student who lived on campus doesn’t eventually complete their degree? It’s discrimination when requirements inherently exclude non traditional students -— whether that is by age, disability, personal goals, or simply chance.

Aren’t we all seeking a degree of self-improvement at OU? Using a definition or stringent requirements for what a student is to exclude those who are different doesn’t make OU a better university. Frankly, it just looks bad.