Professor publishes book about lost ballet

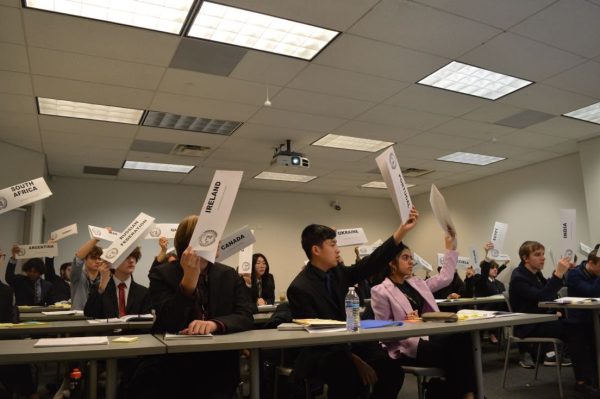

Photo Courtesy Ray Nard Photography.

Steven Houser and Cassidy Isaacson from the Grand Rapids Ballet in Funeral March, Choreography by George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust.

Elizabeth Kattner, an associate professor of dance at Oakland University, is publishing her passion project — a book titled, “Finding Balanchine’s Lost Ballets: Exploring the Lost Work of a Choreographer” in November.

While studying at Free University Berlin, Kattner discovered her passion for researching dance. During her time pursuing her doctorate there, she became particularly interested in the lost ballets of the early 1900s.

“Ballets are passed on person by person, and because very little was filmed that early in the 20th century, most ballets from the era have been forgotten and are no longer performed,” said Kattner.

As her research continued, she became enamored with American ballet choreographer George Balanchine. Ultimately, this fascination led to Kattner writing her dissertation about his career in Russia and how his work developed dance in both Russia and the United States.

“Balanchine trained in the Imperial Ballet in Russia and was an up and coming choreographer in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) in the early years of the Soviet Union,” she said. “In 1934, he moved to New York to establish the New York City Ballet. His work in Russia between 1920 and 1924 was pivotal to the development of dance in both the US and Russia.”

“The dances from the early 20th century were very modern (for that time) and many are no longer performed,” Kattner said. “I went to a ballet performance and saw a ballet that had been lost, and then reconstructed.”

According to Kattner, part of her book focuses on reconstruction as a way to bring back the lost dances. Through this sort of anthropological process, a dance artist takes what materials are available from the lost dances and pieces together the choreography. Kattner’s new book also details historical research and her experience as a dancer and choreographer.

During the six-year publication process, Kattner has stayed busy. She has done a variety of studio research, as well as presentations of her research on ballet. She was even able to use the material she gained from her research in the studio while working with the dancers of the Grand Rapids Ballet. Since 1923, this culminated in the first group performance of a ballet choreographed by George Balanchine entitled, “Funeral March.”

While developing this project, Kattner traveled to St. Petersburg, Russia to work in the St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music, as well as in the Central State Archive for Literature and the Arts. This trip was productive for Kattner not just because it advanced her research, but because it presented a valuable opportunity to practice learning the Russian language.

“Being allowed to work in the archives in St. Petersburg was so exciting,” she said. “It was a great motivation to continue to work on learning [Russian].”

Another occasion for research arose while she was in New York City, where she listened to recordings of ballet performers in the oral history archives of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Her new book has benefited greatly from the more than a decade of research conducted across the United States and Europe. The work Kattner has put in has allowed her to synthesize a variety of textual descriptions with photographs and the study of Balanchine ballets while recreating this forgotten work for readers.

Moving forward, Kattner hopes to continue her research into dance of the early 1900s era. She plans to improve her skills with the Russian language so she can continue to study early Soviet ballet. Her goal is to revive something meaningful for dance scholarship.

“Lost dances do not have to stay lost,” she said. “They have meaning for us today. Maybe not the same meaning as they did for the original audience, but they do have meaning.”