Deaf student shares her story in ASL program

Jenna Varosi-Garavaglia, a former Oakland University student who has lost 95% of her hearing, is now a teaching as an assistant for an American Sign Language professor.

In fifth grade, Jenna Varosi-Garavaglia was moved to the front of the class. She didn’t understand why and asked her teacher.

“He said, ‘You just don’t pay attention without me looking at you,’” Varosi-Garavaglia said.

Little did she know, this was the first sign that her hearing was fading.

It took until the age of 12 for doctors to realize she was missing half of her audible ability. To prove his point, the physician held his hand over his mouth while speaking. She was oblivious.

The hearing has worsened over time, 22-year-old Varosi-Garavaglia is now 95 percent deaf.

While born without any problems, it was found she has a condition called sensorineural hearing loss. This is a permanent form of hearing loss that happens when there is damage to the inner ear, or cochlea, or to the nerve pathways from the inner ear to the brain, according to The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

The damage can come from prolonged exposure to high-intensity noise, according to HearIt.org. The loud instruments Varosi-Garavaglia played in band likely set off the deterioration, she said.

She gave the example of someone who goes to a concert and experiences mild hearing loss for the next few days. In her case, her hearing never came back.

Up until this diagnosis, Varosi-Garavaglia was unaware of any problems. It turned out she had been relying on lip reading to make up for the loss, thinking everyone watched television at volume 30.

Adjusting to a new life

The news was initially very difficult.

“I was absolutely devastated,” Varosi-Garavaglia said. “I remember feeling awkward telling people about it because their first reaction was always that they were sorry, and so I got the impression that it was a sad thing.”

Her depression continued, and she was at her lowest point the year she entered college.

Up until then, she had no access to deaf education and used YouTube to teach herself signs. As she never met anyone who was deaf, she was missing support from someone who had similar experiences. Connecting with people grew difficult, and her friends eventually stopped inviting her out.

Things began looking up when she took her first American Sign Language (ASL) class with Paul Fugate at Oakland University. In just two short years, she was able to sign proficiently. When asked how she learned so fast, she replied: necessity.

“You learn to change a tire pretty quick if no one else is there to help with your flat,” she said.

To accommodate, she’s had to make some changes. This includes using a vibrating alarm clock, a powerful disc placed under her mattress.

“It felt like waking up to an earthquake and really scared me at first,” she said. “Now I’ve slept through it.”

She also recently got a video phone. When she needs to make a call, she’s connected to an interpreter through a camera hooked up to her television. She signs her message, the interpreter then translates it to the third party.

While she’s in a good place now, it took some time to get out of her funk.

One afternoon at a grocery store, things were really put into perspective.

Noticing a man signing to someone, Varosi-Garavaglia approached him and told of how she was newly deaf. In one of her first conversations with a deaf person, she found out that the man was married and had a good job.

“It was in that exact moment I realized being deaf is just a trait,” she said. “It’s like being blonde or having green eyes. It’s who you are. But luckily, this is something that I can be proud of too.”

This concept is demonstrated in how controversial the cochlear implant is among members of the deaf community.

“Deaf people don’t look at deafness as a disability,” she said. “This device makes it seem like it alleviates or cures you.”

Varosi-Garavaglia described how deaf people have an entire culture, from musicians and local leaders, to the National Theater of the Deaf and deaf colleges like Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C.

Recently visiting to scope out the campus, Varosi-Garavaglia said her hands began to hurt from all of the signing.

“It was the first time I understood everyone in the room,” she said.

Another component of this culture is the tight-knit community.

Ninety percent of deaf people are born to hearing families, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. This can be difficult for both parties. Many lose touch with family members once they leave home, so the deaf people they meet become their family, Varosi-Garavaglia said.

Her mission

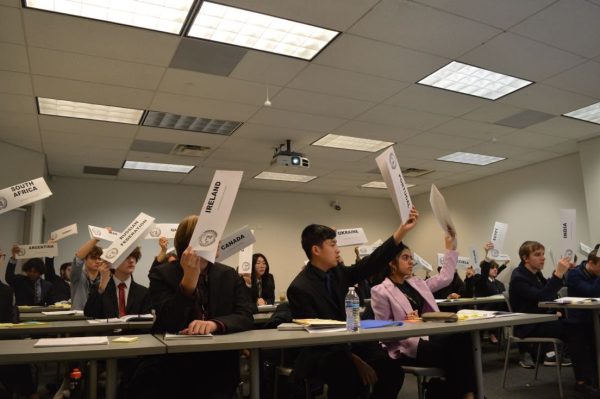

Varosi-Garavaglia has been an ASL teaching assistant at OU for three years and loves being able to share her story with classes.

Students have pulled her aside and asked how she managed to get through those tough times.

“I would tell them that I decided not to be ashamed anymore,” she said. “So many would say they were inspired. Every time I hear those words, I know that I’m supposed to be teaching.”

She feels she has a unique advantage.

“My experience is uncommon — not many lose their hearing that late in life.”

Because of this, she’s helped deaf people learn how to pronounce certain words. It’s much harder for those born deaf to make the connection between written and vocalized words, as they have no previous knowledge of sound to go back on.

She has also been helping students through ASLDeafined, Fugate’s online learning platform with over 300 ASL lessons, each with a different subject, according to its website.

As a deaf expert, she is recorded demonstrating various signs. The site now has over 15,000 of these video clips for users to review and master.

Varosi-Garavaglia said that learning sign language is more popular these days, as deafness is more prevalent in media with television shows like “Switched at Birth”.

However, there is still progress to be made in society.

Hurdles to overcome

One problem is there isn’t a system to ensure open access to communication for the deaf. Varosi-Garavaglia said that while at the hospital, she has known people who waited 12 hours for an interpreter.

“They’re basically telling them they have to wait to know what’s going on.”

And while Disney World recently put captions on all of their televisions, places like Cedar Point only have them on a portion. Therefore, those who are deaf or hard of hearing may be oblivious to urgent announcements.

Varosi-Garavaglia also described how the deaf can face discrimination, like when someone refuses to repeat themselves. In addition, there are still many misconceptions, as a deaf person may be called “retarded” or perceived as rude for “ignoring” others when they simply didn’t hear them.

“Little things like that add up, and we feel left out,” she said.

She noted that a lack of education is often the cause of this ignorance.

A prime example occurred while Varosi-Garavaglia was signing with her friend at a restaurant. The waiter noticed and brought back a braille menu—complete with pictures.

This is why she talks about her experiences whenever she has the chance. She hopes that people will take a little time to do some research, and learn that this is a deaf person’s lifestyle.

“It is not something that hinders their existence — it’s something that enhances it,” she said.

Ultimately, she said, the deaf are not much different than everyone else.

“We see the world through our eyes instead of our ears.”

Karen Heath • Nov 29, 2016 at 9:43 PM

Jenna you are my beautiful niece and I could not be more proud of you. You are a true inspiration to all your family and friends who know you. You have overcome all kinds of adversity throughout your young life and come out so strong and resilient. I know your positive impact on this world around us now and in the future will be amazing…. and all of us who know you will not be surprised by the great things you will accomplish!